Last year, as the coronavirus pandemic swept the world, staffers at the virtual National Women’s History Museum realized a pivotal period was unfolding for women across America.

Women constituted 52% of essential workers, according to a New York Times analysis, which also found that women of color were more likely to be doing essential work than any other demographics. Women also made up about 75% of health care workers in most cities. And they were taking on more work at home, according to one study, which also found that mothers were more than three times as likely as fathers to be responsible for the majority of housework and caregiving during the pandemic — with Black and Latina mothers, respectively, being twice and 1.6 times more likely than white mothers to be responsible for all childcare and housework. By September, 865,000 women dropped out of the workforce, with Black women and Latinas seeing the highest unemployment rates, at about 11% each.

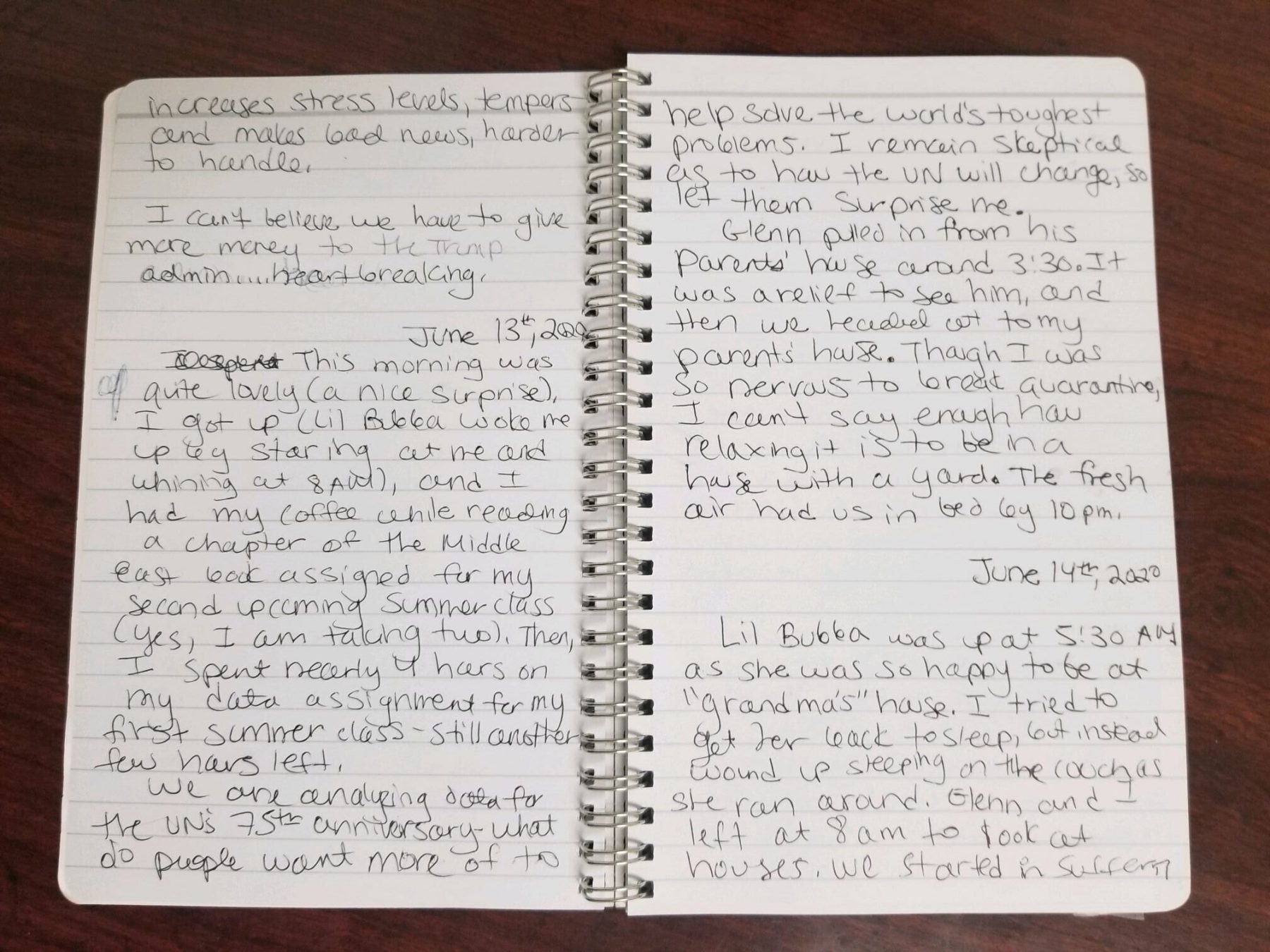

So museum staffers did what any good historians would: they asked women, girls, and non-binary people to record the realities of their day-to-day lives during the pandemic.

Those records are the focus of a forthcoming online exhibition — “Women Writing History: A Coronavirus Journaling Project” — debuting in mid-April, which will feature nearly 300 journals documenting the daily, and often distinctly gendered, impacts of Covid-19. About 1,400 people have signed up to participate, and more journals are expected to be archived throughout the rest of this year, according to Lori Ann Terjesen, the museum’s director of education, and vice president of external affairs Jennifer Herrera.

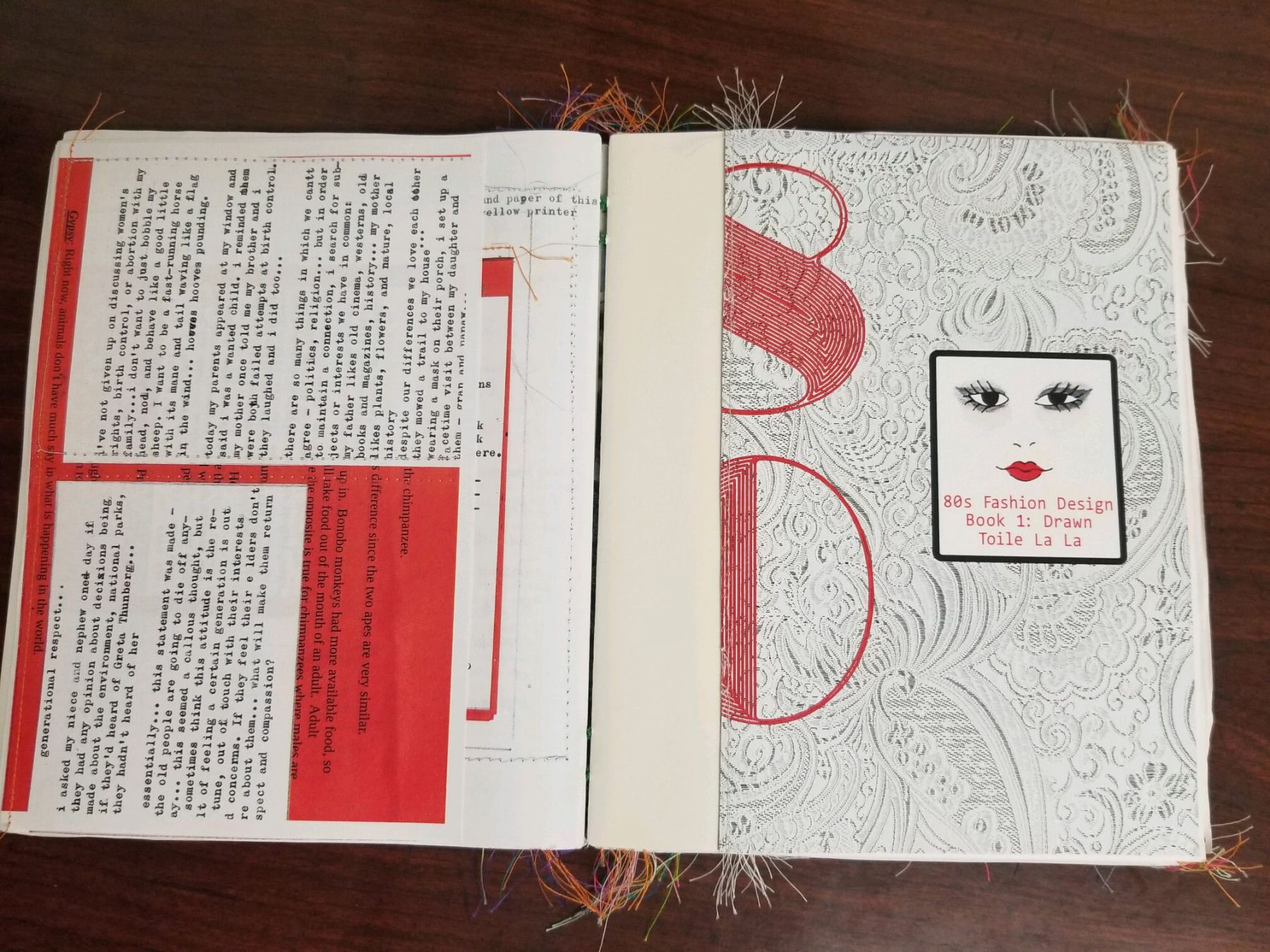

The submissions will span forms, including written entries, voice memos, videos, photographs, and artworks. They’ll also spotlight a variety of women’s, girls’, and non-binary peoples’ lived experiences, from all walks — and ages — of life, making them rich sources of material for future historians, according to Holly Hotchner, the museum’s president and chief executive officer.

“The stories are unbelievably impactful and very moving, [including] everyone from essential workers, to stay-at-home moms, to even younger people,” Hotchner said. “It’s going to be a very interesting archive, and we don’t even know in years to come how much it will be used or how impactful it could be.”

The pandemic also prompted teachers and students across the country to flock to the museum’s site to make use of its many free virtual resources as they adjusted to remote learning: from 2019 to 2020, the website saw an increase of one million visitors, bringing its annual total users to four million, according to Herrera. The site also saw a 125% growth in page views during this year’s Women’s History Month, in March, as compared to last year’s, Herrera said.

The site’s most popular resources include its 150 biographies, which spotlight contemporary women such as Vice President Kamala Harris and Stacey Abrams alongside historical figures including journalist and Black feminist activist Ida B. Wells, Chinese suffragette Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Hispanic suffragette Adelina Otero-Warren, and Indigenous activist Elouise Cobell. Pandemic-particular hits included the site’s ‘Brave Girls’ virtual storytime series, which featured actresses Logan Browning, Gloria Calderón Kellett, and Brianna Brown Keen, among others, reading children’s books centered on themes of equity and inclusion. And a full day of panels, lectures, and other virtual programming were on offer last August to celebrate the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, which technically granted women’s suffrage — though Native Americans, Asian American immigrants, Latinas, and Black women were still prevented from voting for decades to come.

The year-long pandemic was not the first time the museum emphasized the importance of recording — and shaping — history in the making: its leaders were also instrumental in fighting for the forthcoming women’s history museum in Washington, D.C., in part by funding the congressional commission that produced the 2016 report arguing for the necessity of such a space, which the commission recommended naming the American Museum of Women’s History. The measure finalizing the museum’s future existence was tucked into the $2.3 trillion Covid-19 relief package that Congress passed and former President Trump signed into law last December, which also cleared the way for a national Latino museum to be established. Both the women’s history and Latino museums will be Smithsonian institutions.

For Hotchner and others at the helm of the museum, the new space will go a long way towards rectifying the historical exclusions of the perspectives and contributions of people marginalized on the bases of their gender and race, among other factors.

“History has been taught primarily from a white male perspective,” Hotchner said. “You could argue, ‘Why does there need to be a separate museum [for women]?’ It’s because a pretty bad job has been done on covering the history of women and people of color.”

The roles that the National Women’s History Museum’s research and staffers will play in the new museum will be determined in the coming years, Hotcher said. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the women’s history museum will cost $375 million to build over a nine-year period, half of which will be allocated by Congress and half from private fundraising.

But the virtual museum plans to take itself at least partly offline sooner than 2029: its leaders hope to partner with other D.C. museums, beginning in 2022, to offer physical exhibitions and public programming, including lectures, films, and symposia, according to Hotcher. By doing so, its staffers hope to contribute to centering the diverse stories of women in American history.

“Inclusive history is good history,” Terjesen said. “You can’t actually teach good history without including everyone’s voices. Otherwise it’s just a segment of history that you’re teaching, and that’s to the detriment of our future leaders.”