CD Davidson-Hiers, an education and families reporter for the Tallahassee Democrat, has always included her work phone number at the end of her stories. But she never anticipated receiving the amount of texts and calls from readers she did when the vaccine was first made available in Leon County, Florida, in December.

“I had people who didn’t have access to the internet calling me and saying, ‘We read your column. We don’t have access to the Internet and the phone line for the health department is down. What can we do?’” Davidson-Hiers said.

Not knowing where else to turn and desperate to get their shots, hundreds of seniors and their family members called Davidson-Hiers for guidance. Soon, the reporter was operating a makeshift hotline from her apartment in between writing stories in an attempt to help those eligible secure their appointments.

“I’ve spoken to many people who are in tears by the time they call,” Davidson-Hiers said. “The daughter of a woman in her 80s texted me and asked if I could call her mom and talk her through it and when I got on the phone with her mom, she was just sobbing, saying, ‘I should just give up’ and I was like, ‘No, you’re not going to give up. I haven’t given up at this point. Now is not the time to do that.’”

Since the pandemic began, journalists like Davidson-Hiers have been going beyond their job description to aid community members, by helping them coordinate unemployment benefits and vaccine appointments, providing information to help them safely navigate daily living, or even supplying emotional support during a period marked by confusion, panic and grief. The pandemic has not only exacerbated inequalities that have disproportionately affected communities of color and other minoritized groups, but it has also further revealed the government’s inability to take care of its people during a crisis of this scale. Where the government has failed, many journalists have stepped up.

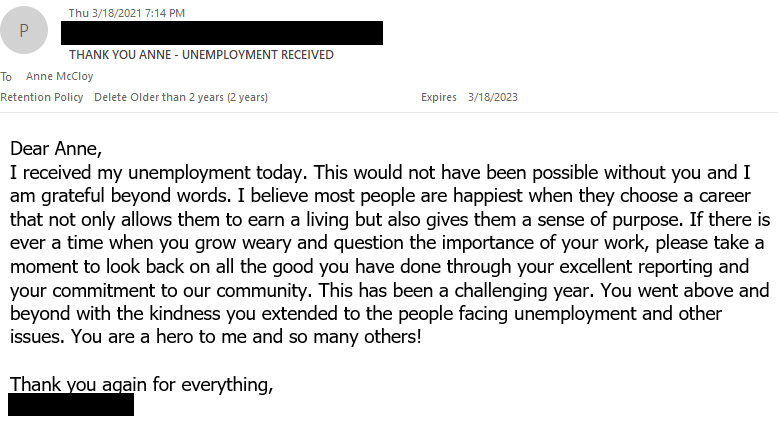

Anne McCloy, an anchor at CBS-6 Albany in New York, is accustomed to digging around for a hard-hitting story, but after reporting about an unemployed man who showed up to her station crying and seeking assistance because he couldn’t connect with the New York State Department of Labor to access his unemployment benefits last May, hundreds of others began contacting the journalist with similar accounts. So McCloy did what she knows best: she asked difficult questions.

During one of Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s press conferences last year, McCloy asked why so many people had been waiting months for their benefits. “We have people calling our news station in tears saying that they can’t get through to the unemployment line,” she said at the time.

Melissa DeRosa, the secretary to the governor, said the office would look into it, then later contacted McCloy, instructing her to forward the information of people who were running into issues accessing unemployment. McCloy combed through her messages and compiled a list of around 200 people to send to DeRosa, but that wasn’t the end of it. Eventually so many people kept reaching out that McCloy was set up with her own inbox at the Labor Department. To date, she has helped approximately 5,000 people connect with an unemployment specialist at the Labor Department and she is still fielding emails, though much less than before.

“The pain of New Yorkers weighed on me and it was the type of thing where you couldn’t sleep at night knowing so many people were in that position with no one to turn to,” McCloy said.

Some newsrooms such as KPCC – Southern California Public Radio and Block Club Chicago have also introduced new technology to make community engagement a bigger share of their work. Both outlets have developed ways for community members to contact their reporters directly with coronavirus-related questions. KPCC does this mainly through Hearken, a community engagement technology platform, while Block Club Chicago mainly uses a hotline, which was inspired by KPCC’s. The questions have been pouring in for both outlets, which are paying added attention to helping those without Internet access and Spanish speakers who have limited access to coronavirus-related resources in their language.

“When it came to setting up vaccine appointments, we got a lot of people sharing, ‘I have this medical condition. I can’t leave the house,’ ‘My mom has this. I need to help her find a vaccine’ and it’s heartbreaking,” Hannah Boufford, Block Club Chicago’s newsletter and hotline manager, said. “It’s devastating day in and day out to help all these people and know there’s so much struggle going on and to know that we’re probably only hitting a fraction of the people in the city.”

Ashley Alvarado, the community engagement editor at KPCC – Southern California Radio, said the station has used similar community outreach strategies during other crises, such as the California wildfires. Yet the quantity of the questions the outlet has received during the pandemic has been astounding. Per Alvarado, the outlet was receiving “hundreds and hundreds of questions” during the first few weeks of the pandemic and on at least two occasions, it received more than 10 questions a minute.

For journalists, speaking with so many people who are dealing with dire conditions while also grappling with a global pandemic themselves has been emotionally taxing.

“Journalism as a whole is trauma-facing, but when you’re thinking about the thousands of questions we’re processing from folks who are scared, who are dealing with loss, who has lost their jobs, or who are fearing eviction, it’s a lot,” Alvarado said.

As difficult as this work has been, it’s also been rewarding. Boufford recalls speaking to a reader on the day the United Center, Chicago’s largest vaccination center, opened appointments earlier this month.

“I was on the phone with someone and they were like, ‘I can’t get through. I can’t get an appointment,’ and then all of a sudden she was like ‘Oh my God, I see appointments.’ And it was just that moment of finally,” Boufford said. “I’m tearing up a little bit thinking about it. It’s heartbreaking, but it’s also really beautiful to help people.”