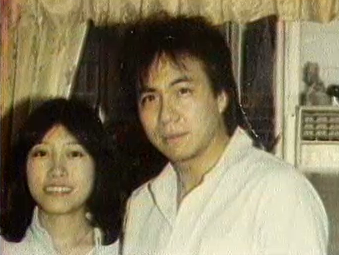

Bayard was 24 in the picture. I happened to see it at my town’s Chinese history museum. The placard read, “1978,” and Bayard was trying to sign up people to vote.

It’s kind of like when other Asian Americans see me on TV. I pointed at the picture of the Asian American civil rights worker and thought, “There he is!…” I feel strange. But glad. But strange.

Bayard and others like him were at the forefront of Asian American civil rights. In May of 1968 — four years after the Civil Rights Act passed — students at UC Berkeley formed the Asian American Political Alliance, marking the first usage of “Asian American.” Before that, we had been told that we were “Oriental.” The students called for uniting a multi-ethnic group under a single tent.

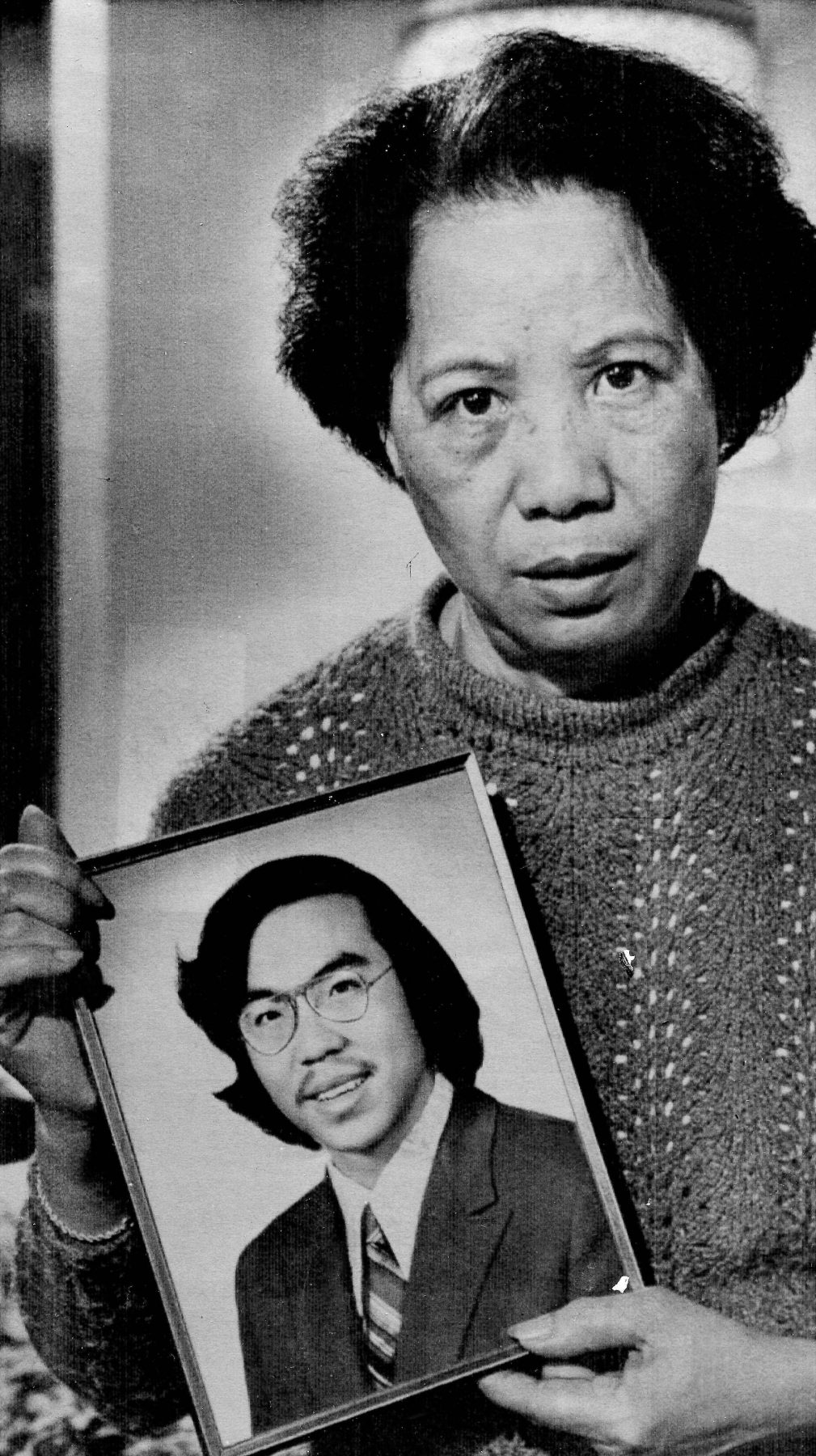

But it was a Chinese American man in Detroit named Vincent Chin who solidified the birth of a “movement” for Bayard and Asian American civil rights.

One night in 1982, a laid-off auto worker and his step-father were out for a drink. At that time, carmakers from Japan were dominating the U.S. market. Looking for someone to blame, they targeted Chin. It escalated. They pushed him to the ground in front of a McDonald’s, beating him to death with a bat. People just watched. Vincent was just out for his bachelor party, didn’t work for a car company, and was of Chinese descent.

Journalists from California such as Helen Zia flew east to call for the prosecution of the assailants. Reporter Ti-Hua Chang and photographer Corky Lee also flew in from New York to document the story. Bayard, like thousands of others, marched in the streets calling for justice.

The two assailants were eventually caught, sentenced to three months probation, and a $3,000 fine — “$3,000 License to Kill,” as some early Asian American activists called it.

That’s the way it was in the 1800s when construction worker camps full of Asians would get pillaged at will. Had a bad day, got a little drunk, didn’t like the job situation? Go beat up and kill the Chinese in the work camps. It’s okay, they were indentured servants and by law couldn’t testify against you anyway. No price to pay and you’ll feel better afterward.

Back to Vincent: his death was a turning point for the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. So is today.

The last five years have been painful to be a journalist of color again. We’ve stood in the streets of Ferguson, Baltimore, New York and Minneapolis, telling stories of Black men being killed or beaten because of the color of their skin.

Now, after the killings of eight people at Atlanta-area spas, six of them AAPI women, is another such moment. And it’s not just the spa workers in Atlanta. It’s also the Asian senior citizens who have been harassed, assaulted —and even killed — in the street. There have been 3,800 documented reports of hate incidents in the past year against Asians in America. This number is likely an undercount, since it only includes self-reporting and we Asians don’t like to report. That’s part of the problem.

So in this moment we have to ask — what happened between 1968 and 2021?

We didn’t finish what we started. Instead, the birth of the Asian American civil rights movement suffered from a thousand cuts.

Each time kids like me were called “Kung Fu Kid” growing up, and didn’t fight back — one cut.

Each mocking or degrading media portrayal — one cut.

Each “model” Asian American passed over for leadership in business and media — one cut.

We must stop the culture of giving a free pass to attack Asians in America. The culture that makes it a sport, that mocks them, then laughs about it, that puts us up as a “model minority” when it’s convenient then puts us down as second class, perpetual foreigners. But we also must stop the culture of being people who won’t speak up, fight back, or punch back.

Reporting on my community for the last 15 years at CNN Worldwide and now, MSNBC / NBC News, has been an honor and a difficulty. Most of our country didn’t have an appetite for it. But now there is some, built on the shoulders of Zia, Chang, Lee and many others.

I remember when Bayard would come to family gatherings, whooping up the dander about “Asian American this, Asian American that.” I didn’t pay much attention to my older cousin at the time. I thought he was a little crazy. We don’t take on activism careers. We don’t organize like that. And we don’t get so vocal.

Well, cousin Bayard, you were right all along.

It’s time to stand up for the Asian American movement.