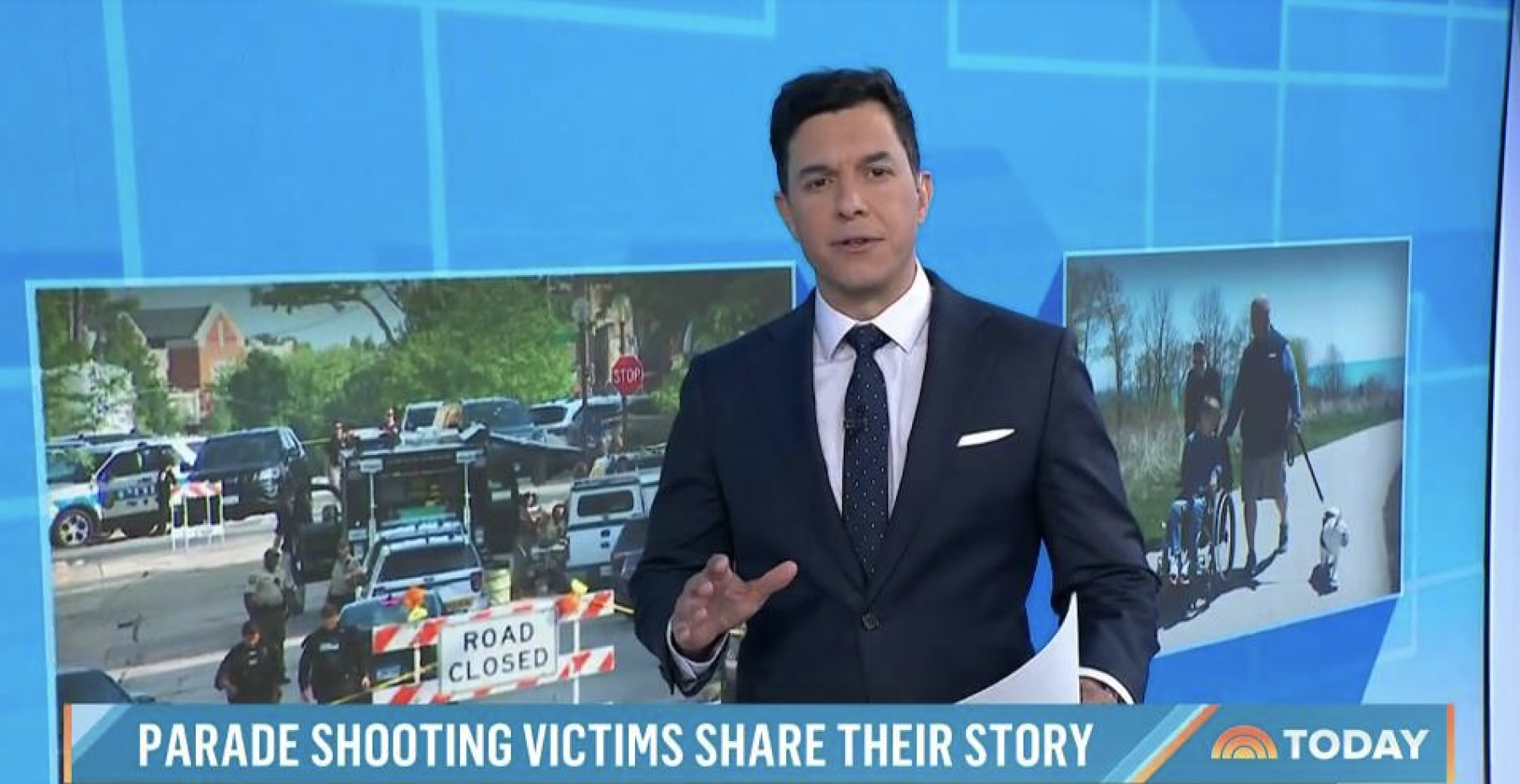

NBC News Senior Correspondent Tom Llamas had just reported on the one-year commemoration of the Uvalde massacre when he confirmed he would be covering the aftermath of another tragedy. The mother of a boy paralyzed in last year’s Fourth of July shooting rampage in Highland Park, Illinois, had agreed to an interview.

“It was just a rough, rough week,” said Llamas, “Top Story” anchor and father of three. “You want to run home to your kids and hug them and be like, ‘You’ve got no idea how lucky you are.’”

Llamas said he also briefly questioned whether audiences would tune in to such traumatic back-to-back coverage. “I was talking to our entire team, like I don’t know if I want to do this.” But the team prevailed, and Llamas went on to conduct a heartbreaking yet inspiring, exclusive interview about tragedy, resilience and the power of family.

“You can’t forget these people,” he said. “I’m glad that my team pushed back.”

Even for the most veteran reporters, covering mass shootings and their aftermath is never easy. Nor is it simple. There’s an inherent tension in our job as journalists to hold our audience’s attention as we report on, and make sense of, the events around us. We must also make sure not to exploit survivors or inadvertently encourage new attacks.

“What lay people don’t appreciate often enough is how much time newsrooms spend navigating those tensions,” said Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

We in the NBCUniversal News Group Standards Department can’t give our teams a paint-by-numbers guide to getting it right. Journalism doesn’t work like that. But below is guidance to achieve the strongest coverage possible.

The 3 pillars of covering mass shootings

When we talk about editorial standards in our coverage of mass shootings, we often focus on the initial phase of our reporting — the “who, what, when, where and why.” It’s an important pillar to get right in a timely manner, especially for broadcast and streaming channels.

Yet it’s only the first of three.

There’s also what Shapiro calls Act 2, or the second pillar, “connecting the dots and following the long arc of the aftermath and recovery.” That includes following up on the initial reporting: how the community is coping in the days, weeks, months or even years after a tragedy (like Llamas’ interview in Highland Park), as well as stories of basic accountability. For example, did law enforcement respond in an appropriate and timely manner? Were important signs missed?

Then there’s the third pillar: the broader social and political implications of –– and context for –– the violence. Each of these pillars requires different standards considerations.

At all stages, we want to center coverage around the victims and survivors — not just their last moments of terror, but their full, complex humanity. Even in stories focused on the legal process, we should strive to include the victims by name, rather than simply as part of a death toll. That’s what keeps coverage of these tragedies from becoming rote or normalized.

Pillar 1: What to consider in initial reports

In the first stage, we’ve gotten better at understanding how our coverage might spur copycats. You might recognize the name Dylan Roof, the white nationalist who murdered the newly ordained Rev. Myra Thompson and eight other Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. But it’s likely you don’t know the name of the white man who fatally shot 10 people in a racially targeted attack last year at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York. That’s because many news outlets, including NBC, have stopped unnecessarily repeating shooters’ names to avoid glorifying them and their violent attacks.

Limited research exists on combating gun violence, or the role of media coverage in the rise of mass shootings. There’s not even a single definition of “mass shooting.” NBC News generally relies on numbers from the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive, which cover all shootings of four or more people, not including the perpetrator.

We do know the media tends to focus on active shooter incidents in populated areas, and the research that does exist suggests these perpetrators may be influenced by what they learn about other attacks through traditional, social or other media.

If we want to avoid sensationalizing these perpetrators, we need to pay equal attention to the visuals, especially footage or images that show the shooter “in position” that could glorify them as some kind of outlaw.

We also want to steer clear of reductive explanations about motive, particularly from people who might not know the perpetrator well but may be the most willing to speak early on. Shapiro cites journalist Dave Cullen’s “Columbine Rule.” Essentially: “a lot of what you find out in the first 48 hours turns out to be bull—.”

When we do get a perpetrator who leaves a trail of words, we want to avoid just reporting angry ramblings, or repeating hate speech or calls to violence. We also generally avoid the term “manifesto,” which suggests a coherent and logical argument, often missing from these screeds. In some instances, we may want to characterize or even briefly quote newsworthy information relevant to the investigation. But killing people shouldn’t be the criterion for getting a perpetrator’s words on air or in print.

Then there’s how we talk about mental illness. About 20% of Americans live with mental health illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions; also, more than 20% of teens have experienced a “seriously debilitating” mental illness. That doesn’t mean they will commit a crime. Mental crises should not be conflated with violence. Like suicide, most shootings occur for a combination of reasons, often a confluence of transient means and a transient state of mind.

Obviously, we can’t ignore the gunman in coverage. We should instead report on the perpetrator with caution and purpose.

Poynter Institute Senior Vice President Kelly McBride, who chairs the Craig Newmark Center for Ethics and Leadership, puts it bluntly: “Most stories don’t need to spend a lot of time on the gunman. But some do. Where did he get the gun? Who knew? Did anyone intervene? What behavior patterns can we deduce?”

Pillar 2: Returning to the community

As we follow communities affected by this violence, additional standards considerations arise. The criminal justice process provides news pegs. So do the one-year or five-year markers of the attack.

Rather than parachuting in and out on the day of these commemorations, we can create meaningful and exclusive coverage by developing pieces that tell big-picture and more in-depth stories about accountability, rebuilding and the lingering effects of trauma. Using these markers as jumping-off points, rather than as the story itself, also helps us avoid retraumatizing survivors.

“We need to be very careful when we are part of that anniversary reporting not to be part of people re-experiencing that lack of safety,” said Shapiro. “The terror of the day and of the week after includes losing control of the story to a zillion out-of-town reporters and their satellite trucks.”

The language we choose is important. It’s worth reflecting on whether our go-to word choices are the most accurate and sensitive. Life is unlikely ever to return to “normal” for many survivors. It may return to the familiar. Communities may not “heal,” but they may become more resilient. People may never “move on,” but communities may move forward. Increasingly, survivors are calling on journalists to refer to commemorations rather than to “anniversaries,” which often connote celebrations or natural life-cycle events.

Pillar 3: Zooming out

Sometimes the most obvious threads can get lost. There’s one thing all mass shootings have in common: guns. As journalists, we should keep digging into what gun laws are on the books, how well they are enforced and what evidenced-based proposals are most likely to reduce these tragedies. For example, NBC News was recently able to tie a longer investigation into ghost guns to the news peg of last month’s Philadelphia shooting involving two of these weapons.

We should also continue to lean on accountability and report on the state and federal officials who set the political agenda. Gun violence kills about the same number of people each year as sepsis but receives less than 1% as much in research funding.

Zooming out further may require deeper dives into the role of misinformation, and how individuals can become radicalized often through online forums that encourage racism, misogyny, homophobia and other forms of hate. We need to pay attention to the increase in alienation in our country and other forces that can lead to this extremism. Poynter’s McBride says covering mass shootings requires covering the state of mental health care, particularly among young people.

“The adjacent conversation to how to prevent mass shootings, is how to prevent suicide,” she said. In fact, suicides by gun and individual homicides still far outpace deaths by mass shootings, which produce a small fraction of gun fatalities.

And as these events multiply, we have an ethical obligation to talk about which mass shootings we cover and why. Those that occur in public spaces may well merit more attention, as may shootings at schools, churches and other social institutions assumed to be among society’s safe spaces. But Shapiro cautions, “We want to make sure we aren’t validating one life over another, or validating or even romanticizing one kind of a shooting over another.”

These are not the conversations to be had when we are running out the door to the next tragedy. In those crucial moments, Llamas recommends just picking up the phone, talking to producers, editors and the standards team. And he urges his fellow journalists, no matter how hard, to keep telling the survivors’ stories.

Talking with his “TODAY” colleagues about his interview with Highland Park mom Keely Roberts and her 9-year-old son, Cooper, Llamas said: “This little boy, he had so much joy. It just jumps out at you. We had to tell the story so people don’t forget.”

🔺 How Journalists Can Take Care of Themselves 🔺

With the rise of mass shootings, many journalists are covering these tragedies multiple times each year, if not each month. It’s important that journalists feel comfortable raising their hands and saying, “I need to sit this one out,” without fear of retribution.

Llamas says it’s also important to remember it’s not just reporters who experience the trauma. “The person that’s recording this through the camera, listening to everything…. the bookers have a lot of pressure on them to find these families,” he notes. “Everyone is feeling the same thing you’re feeling.”

The local reporter standing next to us at the press conference may feel even more. Journalist Priscilla Aguirre kept reporting on the Uvalde shootings even after tweeting that her dad informed her one of the victims was her 10-year-old cousin.

Below are some links to self-care resources for journalists covering trauma:

• Self-Care & Peer Support, Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma

• “Reporting and Resilience: How Journalists Are Managing Their Mental Health,” Nieman Lab

• “How Journalists Can Take Care of Themselves While Covering Trauma,” Poynter