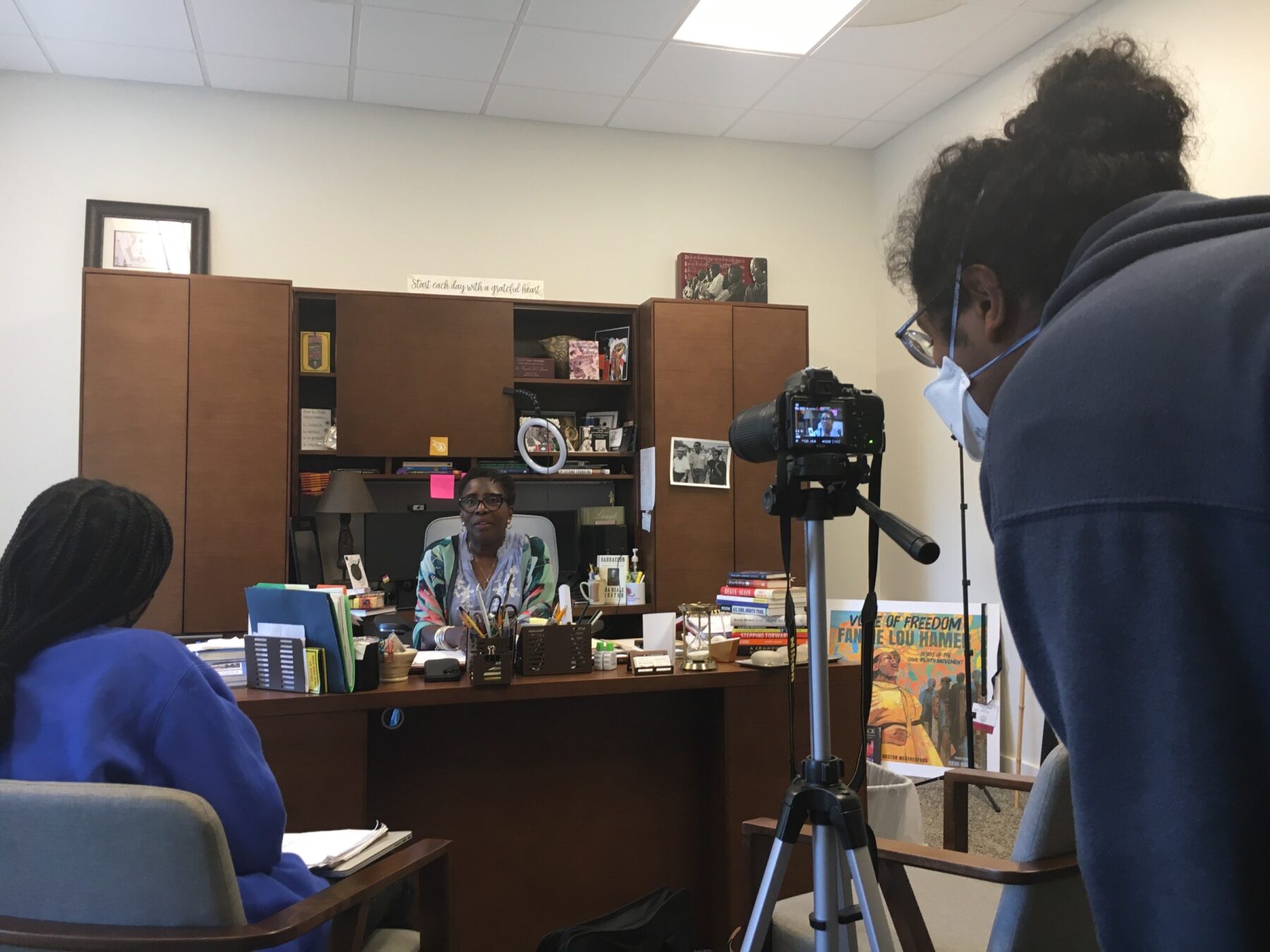

We didn’t know what to expect as we drove through the cotton and soybean fields of western Mississippi and rolled into Jackson, the state capital. We were interns new to the area, hurrying out of the blazing Southern sun, shouldering cameras, microphones and an assortment of tangled wires. Interviewing the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum’s executive director, Pamela Junior, was one of our first assignments. We had been tasked with building a digital storytelling database for the Mississippi Delta National Heritage Area — and we wanted to do the project justice.

For the next hour, we listened to the passion and power in Junior’s voice as she spoke of lesser known civil rights legends, such as Oseola McCarty and Endesha Ida Mae Holland. Junior’s stories were punctuated by a metallic jingling that pierced the museum’s silence every time she gestured with her hands. “When you hear this,” she said, twisting her arms, each wrist adorned by silver bangles, “what you’re hearing are the sounds of the chains. These are sounds of the chains that my ancestors wore. Everything that I do … I have to honor them. … It keeps me motivated, it keeps me going, because I know there’s work to do.”

Junior’s words set the tone for how we would continue our journey of building the archive. She reminded us of the importance of doing this work, the importance of making noise and the importance of raising awareness for these stories.

Despite its name, the Delta is some 300 miles north of the great river’s gaping mouth on the Gulf Coast, stretching from Memphis, Tennessee, to Vicksburg, Mississippi. The flat expanse of land boasts some of the world’s richest soil, deposited over millennia by the flooding and receding river. Because of its history of enslavement and plantation economics, the Delta remains a majority-Black area and one of the poorest regions in the country. It is also considered by many to be the birthplace of the civil rights movement. The Mississippi Delta NHA works to preserve and examine this region’s rich culture and history by distributing federal funding to community organizations across the region.

This project was designed to “create space for sharing these important stories with anyone, anywhere who wishes to learn about them and be inspired,” said Rolando Herts, its executive director. It’s part of the NHA’s broader goal of “empowering underrepresented communities to own and tell their cultural heritage stories,” he said.

Working on the Civil Rights Heritage Archive was daunting because of its significance. We were new to the area; we would only be staying for a few months, and yet we were supposed to document decades of stories about trauma and exploitation in a place neither of us was from. How were we supposed to share these stories properly? How could we avoid commodifying the traumatic realities of how Black communities have struggled and continue to struggle for freedom in the Delta?

For answers, we started searching academic journals, guides to oral history, books and other publications. We certainly learned important lessons from our research — like how the Delta’s agricultural economy is still governed by logistics of plantation production. But the answers to these questions ultimately revealed themselves when we refocused on building personal relationships with the people we interviewed and listening with intention.

We talked to Reena Evers-Everette, daughter of civil rights leaders Medgar and Myrlie Evers, who reflected on how her mother protected her family and continued organizing after Medgar Evers’s assassination. Mary Frances Dear-Moton, daughter of activist Rachel Parker-Dear, recalled witnessing her mother help the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. escape town after an exploding bomb jeopardized his safety; the following day, she was arrested for aiding the civil rights leader.

Even though we were operating on a tight schedule, we consciously chose to not make our first interaction with our community partners be from behind a camera. Instead, we joined them for breakfast or visited them at their place of work. Not only did this give us the privilege of getting to know these changemakers, it also improved the quality of what we added to the archive — our partners felt far more comfortable sharing stories with people they knew and trusted.

It became clear to us very quickly that the struggles Black communities face in the Delta are far from over. Each of our partners reflected on the positive changes that they have organized over their lifetimes, but each also noted that much remains to be done. The Delta’s severe poverty, lack of economic development and persistent segregation were common themes in our conversations. In a time and place where exploitation is still the economic norm, the Delta continues to be a significant site of communal resistance. Keena Graham, superintendent of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers National Monument, told us the civil rights movement was led by “ordinary people doing extraordinary things.”

During our time in the Mississippi Delta, we were shown that its beauty lies in the intangible. The soil that you stand on may have been tilled by a family burdened by enslavement. When you look up at the night sky, it is as if you are drowning in stars — stars that may have guided that same family to freedom. When you listen to the Delta blues, you may hear that family’s sorrows ring out, accompanied by a walking bass line. Even if many of the stories that exist in the land, the sky and the music have been lost to time, their impact and legacy remain.