It was during the height of the Black Lives Matter protests that I suddenly discovered the ideological rift between my father and me. We’re Vietnamese immigrants who came to this country when I was 11. When we first arrived, it was easy to believe in America the way my father did. He saw the U.S. as a country that presented life-saving opportunities and had an immutable conviction that there were no problems that couldn’t be solved.

But once millions of people began taking to the streets to protest the police killing of George Floyd last year, I was shocked at how different our perspectives had become on a seemingly non-controversial movement, and I was exhausted from having to exhaust my limited Vietnamese lexicon to discuss the socio-economic nuances tied to race in America.

Ideological and linguistic roadblocks are an all-too-common experience for many first-generation Vietnamese Americans and their parents everywhere in the diaspora. But that’s only half the story. Though my father thankfully did not buy into the ecosystem of disinformation online the same way that my friends’ parents did, our disagreements prompted me to do research on what our elders consumed online, and it opened my eyes to an information crisis besieging my beloved community.

A historically conservative voting bloc, McCarthy-style politics and anti-communist sentiments created the perfect groundwork for Donald Trump, who promised to take a hawkish stance against China, a stance that Vietnamese people have long supported. For many older Vietnamese Americans, this marked where Trump and his misinformation went viral in the community.

Donald Trump injected fake news into trauma-ridden immigrant communities the same way he did for the rest of the country: by tapping into their deepest paranoia and their inherent fear of being replaced, and by solidifying their resolute belief that any policy proposal left of center will plunge their adopted country into “communism.” It is then easy to see how this volatile and complex history has paved the way for less scrupulous YouTube pundits and media organizations, such as New Tang Dynasty or The Epoch Times, to reap massive profits off of Asian communities’ fears, through sensationalized and outright false news.

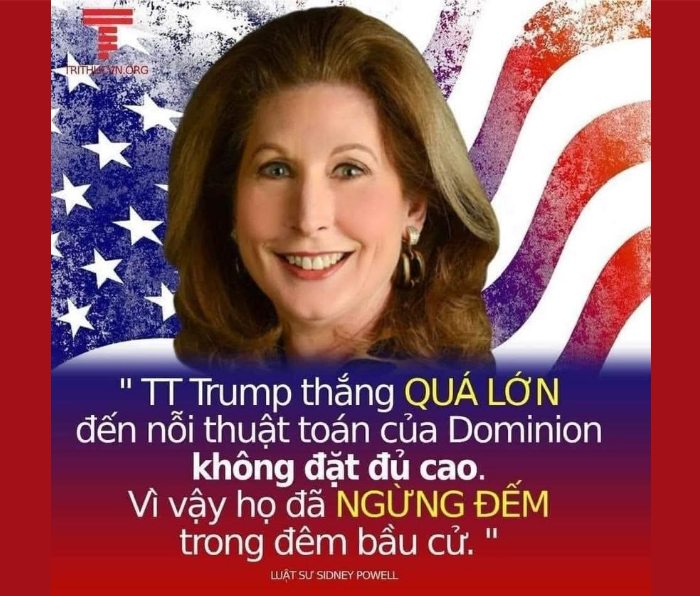

When several states recounted their results of the 2020 presidential election, old, blurry videos of suspicious looking black boxes, and of a Russian ballot counting site being passed off as one in Wisconsin, were shared hundreds of thousands of times on popular Vietnamese Facebook pages and believed by millions. Days after the race was officially called for Joe Biden, The Epoch Times continued to publish false electoral counts favoring Trump. On YouTube, pundits with no relevant background, such as Tran MaicoUSA, prolonged Vietnamese Trump supporters’ hopes months after the election by peddling fake news about ballot recounts and offering dishonest analyses to the audience, but racking up hundreds of thousands of views per video from viewers anxious for a miracle.

So how can we solve this issue?

To combat misinformation within the Vietnamese-speaking diaspora, I co-founded The Interpreter (Người Thông Dịch) with my college friend Jady Chan, based on the observation that Vietnamese people consume U.S.-centric news primarily through articles and posts shared on Facebook.

The Interpreter is a news aggregator that curates think pieces and translates English-language news articles from credible outlets into Vietnamese to help lower the barrier of access into American politics, and to provide a trustworthy alternative news source to unverified streams of information online. Through this project, we’re trying to build a generational bridge and empower the diaspora by lowering the language barrier and making knowledge more accessible.

So far, reviews from the community have been overwhelmingly positive. We’ve heard stories from young Viets who hooked their parents onto The Interpreter, as well as general thanks from older, more liberal uncles and aunties who have been desperately seeking Vietnamese sources to back up their arguments with conservative peers.

We’ve also generated a significant amount of press due to the unique model for news literacy that we built. By promoting the project to popular Vietnamese Facebook groups and on TikTok, we’ve racked up thousands of readers per month, while attracting constant applications from bilingual Vietnamese speakers seeking to volunteer their efforts, because they see our project as beneficial — even necessary — to the future of our community.

It’s important to highlight that I didn’t graduate from college with a degree in journalism, nor did I have any prior experience in media. I co-created this organization with the simple conviction that if nobody else will do it, it would have to be me.

But this simple-minded initial approach to combating fake news makes me a strong believer in the simplicity of the solution. The Interpreter does not have to remain a project within one immigrant community. Our translation and editorial processes can easily be replicated, modified and reinvented in different languages, in ways that can best serve each immigrant group, by just about anyone who has love for their communities and wants to lead the change from within.

Misinformation aimed at any American threatens the very foundation of our democracy, and immigrant communities deserve a fair chance to make electoral decisions grounded in the truth. Every year, the U.S. gains hundreds of thousands of new voters through the naturalization process. Asian Americans continue to be the fastest growing segment of the electorate, ballooning from 4 million voters in 2000 to 11.1 million in 2020. Latinos, meanwhile, make up the largest group of immigrants in the U.S., playing key roles in swinging election results. Last year, the Latino electorate cast more than 30% more votes than in 2016. With these trends in mind, misinformation can very well fuel the outcome of our next midterms and general elections, until a government truly by and for the people is but a distant past.