![Newspaper advertisement offering reward for the return of an escaped slave to his oppressors, Princess Anne, Maryland, April 1, 1861. Text reads: $50 Reward. Ranaway from the subscriber on Tuesday Morning, 26th Ultimo [last month], My negor boy calling himself Severn Black. The said negro is about 5 feet six inches in height, chesnut color, has a scar on his upperlip, downcast countenance when spoken to, blink-eyed, showing a great deal of white, long bushy hair, is about twenty years old, had on when he lefta [sic] blue fustian Jacket, pantaloons of a greyish color, blue striped shirt, a black slouch hat and shoes nearly worn out. The above reward will be paid by me for the apprehension and delivery of the said negro in the county jail.](https://nbcuacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Runaway_Ad_4x3.jpeg)

In the ongoing conversation about reparations, media reparations shouldn’t be overlooked.

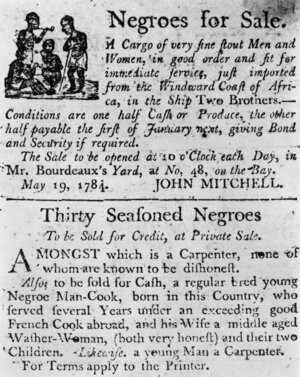

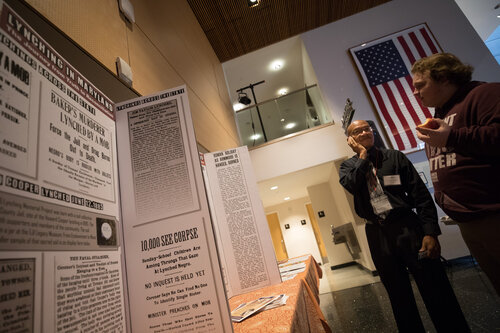

The harms that created the need for media reparations date back to the normalization of chattel slavery and human trafficking in the United States. The first presidents and those deemed “founders” of the country ran advertisements for missing and runaway enslaved people. These ads contributed to the profitability of early newspapers. Media narratives later contributed to the Wilmington Massacre, Tulsa Massacre, and other kinds of mass Black death.

In “The Warmth of Other Suns,” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Isabel Wilkerson describes this deadly role that newspapers once played in promoting violence against Black people. “Newspapers were giving black violence top billing, the most breathless outrage reserved for any rumor of black male indiscretion toward a white woman, all but guaranteeing a lynching,” she writes. “Sheriff’s deputies mysteriously found themselves unable to prevent the abduction of a black suspect from a jailhouse cell. Newspapers alerted readers to the time and place of an upcoming lynching.”

These harms aren’t just a thing of the past. As of 2017, less than 1 percent of full power TV stations were Black-owned and controlled. Out of 11,000 commercial AM/FM stations, only 217 were Black owned. The most recent survey data from the American Society of News Editors showed that Black journalists make up only 5.6 percent of newsroom staffers at daily publications and online sites and 4.6 percent of newsroom leaders. And when it comes to narratives around Black lives, a study conducted by Color of Change showed that while 51 percent of arrests by the NYPD in 2015 were of Black people, 75 percent of people presented as perpetrators of crime by local media were Black.

In an effort to alchemize these harms, community members are now sharing dreams and visions for a future where they no longer exist. In this future, Black people and communities have the capital and resources necessary to own and control our own stories, from ideation through production and distribution into the world. We are no longer forced to fight back against news and entertainment defined by singular regressive stereotypes that then become the justification for policies and practices that poison our communities, cage our people and shorten our lives.

In this vision, media is abundant with the fullness of Black personhood. Black media-makers are abundant with opportunities, care and material means.

One of the ways to make this vision a reality is through media reparations. As director of Media 2070, an organization that advocates for media reparations, I see it as one of the few pathways to a just media system, and therefore, a just society.

There are many perspectives on the definition of reparations. But most importantly, media reparations are both a process and a series of destinations, including and beyond redistribution of wealth.

Liberation Ventures, a field-building organization that supports the reparations ecosystem, developed a framework that outlines the four elements necessary for comprehensive racial repair. It builds upon insights from organizations including the United Nations, Movement for Black Lives, National African American Reparations Commission, National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, and prominent thinkers Sandy Darity and A. Kirsten Mullen, co-authors of “From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.”

The components include:

Reckoning: The act of dealing or grappling with something as an individual, institution, or society, where success looks like curriculum change, public conversation, narrative shifts and/or research to unearth injustice. Meredith Clark’s reparative journalism model offers an excellent framework for what’s possible here.

Acknowledgement: Admission of responsibility and apology for the atrocity, and guarantee of non-repetition, where success looks like transparency about the reckoning process and apology. We witnessed several examples of this kind of acknowledgement via newsroom apologies in 2020 and 2021.

Accountability: Obligation and willingness to take responsibility for individual and institutional wrongdoings, where success looks like financial resources committed, acting as an accomplice and/or institutional capacity building. This is something seen in the Reddit board transition from Alexis Ohanian to Michael Seibel.

Redress: Acts of restitution and rehabilitation, proactive steps taken to embed racial justice into systems, where success looks like financial compensation, meaningful transfers of power, multiracial democratic governance and congruence. There is still so much more of this to experience across our media system.

Comprehensive media reparations must include each of these elements. While media reparations include reparative action across media and technology public policy, it also includes reparative policies and programs within and amongst media organizations and philanthropies for the harm they’ve caused Black journalists, media makers and broader Black communities.

One example of comprehensive media reparations might be a news organization studying the ways its narrative, representation, and ownership have harmed and continue to harm and leave out Black communities and Black journalists; acknowledge that publicly; gathering recommendations from Black communities in their media market for what transforming harm needs to include (it might help in this instance to partner with an organization to do this); enacting those recommendations plus others that create multiple levels of accountability and redress through processes like redistribution of profit or transfers of power; and building in mechanisms for accountability, harm reduction, more nimble harm transformation and iteration into the future.

For a government agency such as the FCC or a social media platform or a philanthropy serving Black communities, and specifically Black journalists and media makers, this process might include different specificities, but the general process would be the same.

Media 2070 is a campaign for media reparations built and led by the Black caucus at the national advocacy organization Free Press, flanked by organizations and individual media makers and activists across the U.S. and globally working to co-create a media system and society where all people thrive. Since launching in 2020, Media 2070 has been building a consortium of scholars, media-makers, community artists and activists to make the work of media reparations real while maintaining an emergent living archive of media harm and speculative futures.

The journey toward that future involves initiatives anchored in the desires and possibilities birthed by individuals and organizations across the media reparations movement. Media 2070 issued a call to newsrooms and media organizations to sign a Pledge to Care for Black Communities and Journalists. So far more than 30 organizations have signed and the movement is growing. We also joined Democratic Reps. Jamaal Bowman, Valerie Clarke and Brenda Lawrence in urging the Federal Communications Commission to initiate a study of racial inequity in the agency’s history of media policymaking. Grassroots organizations as well as Senate champions are joining this call, and we anticipate a robust federal investigation in keeping with President Biden’s executive order on advancing racial equity.

Media reparations are long overdue, but the possible futures are bright and near because of the work happening currently and the Black and Indigenous histories it builds upon. Joining in to build the strength and power of that work allows the reckoning and transformation required for the just society we all need.