Maleeyah Frazier, now 18, remembers when campus police officers used to roam Hamilton High School in the Castle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. Their presence made her feel uneasy and scared, an extension of the high-speed police chases she witnessed on residential streets and the police pointing guns in her neighborhood.

“As students, we see the police hurting our own communities,” she said. “Then we go to school, which is supposed to be a safe learning space, but instead, we’re greeted by school police officers.”

Jailynn Butler-Thomas, who attended Dorsey High School in nearby Crenshaw, also remembers police trying to de-escalate fights on campus, only to sometimes make them worse. During one fight in 2019, police began pepper-spraying students who were walking to class, she said. “Students were running to the nurse’s office to try and get help, but there was no one there,” she said. “We had money being spent on school police, but we didn’t even have a full-time nurse to take care of us.”

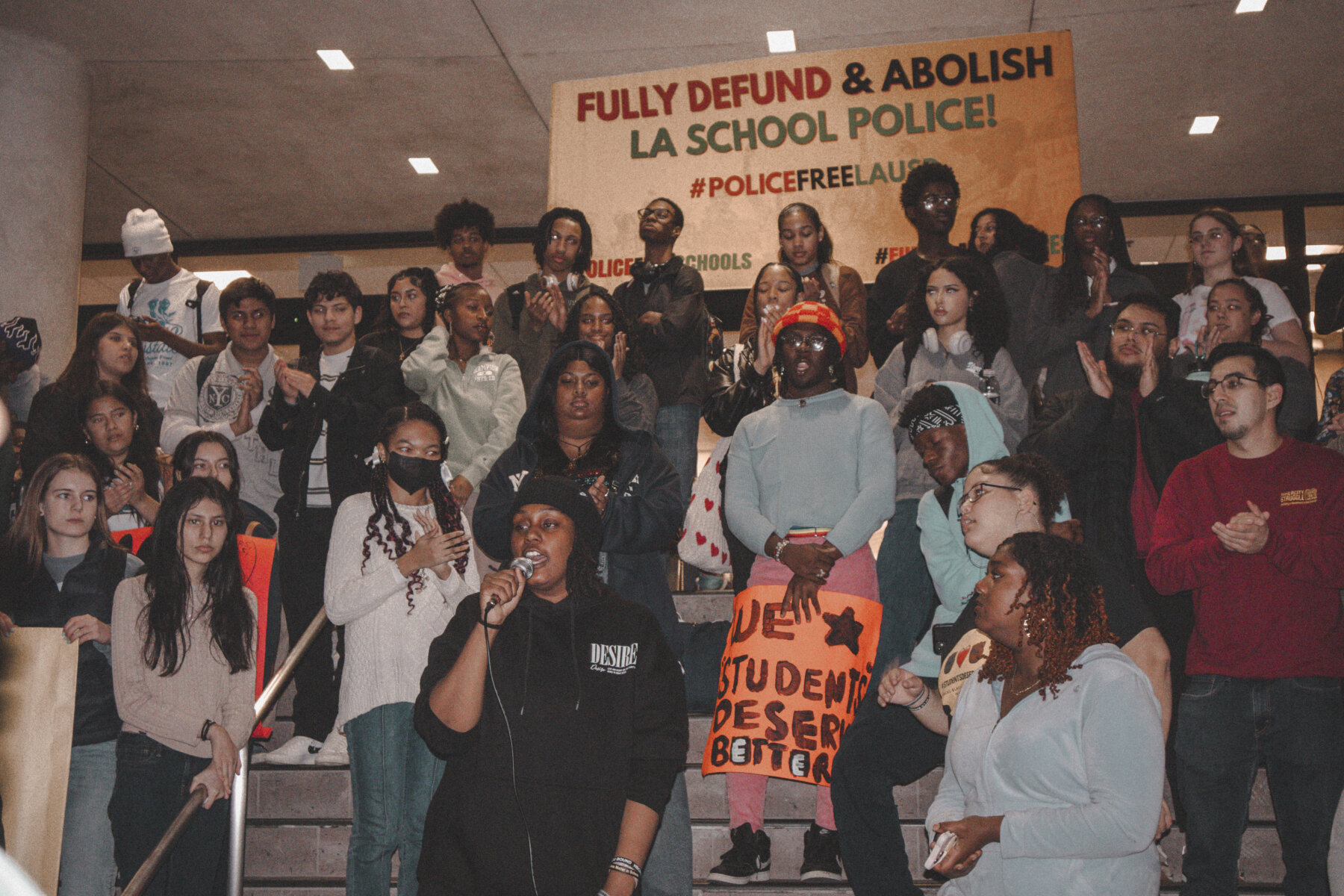

Butler-Thomas and Frazier are part of Students Deserve, an organization of around 250 students who advocate ending school policing and student criminalization in the Los Angeles Unified School District. The youth-led group has been fighting to remove police presence on campuses since 2013, arguing that police disproportionately surveil and harass Black and brown youth — and has had great success.

In 2019, Students Deserve ended random searches on students; in 2020, it ended police use of pepper spray on all district campuses. Most notably, as part of the Police-Free LAUSD coalition, the group helped defund $25 million from the LA police budget — the largest amount ever defunded from a school police department. They then successfully pushed for the school board to reinvest those funds into a new Black Student Achievement Plan, which offers academic counselors, climate advocates and psychiatric social workers for Black students.

“What makes our victory significant and historic is that we took money from school police and then redistributed that money directly to supporting Black youth,” said David Turner III, co-founder of the Police-Free LAUSD Coalition. “We created radical change.”

While the district was one of dozens that stopped or cut school policing programs after police killed George Floyd in 2020, some districts have since reinstated police. Students Deserve, meanwhile, continues to reinvest in historically marginalized students. The Black Student Achievement Plan budget was expanded by $26 million last year and the program has been codified into the 2023 United Teachers Los Angeles union negotiations. Police still aren’t stationed on campuses. While challenges remain — there are reports of police pepper-spraying students after being called to campus — advocates are hopeful that because of their perseverance, strategizing and collaboration, the changes are here to stay.

When Frazier stepped back onto campus after the defunding in 2021, she felt the breadth of what the group had accomplished. “I thought to myself, ‘You really did that,’” she said. “We actually did defund the school police and allocate that money to resources for Black students.”

How Students Deserve successfully defunded school police

To understand how Students Deserve was able to achieve a historic school police defunding — the Los Angeles School Police Department was the first school police unit in the U.S. formed in 1948 — it’s important to recognize the public awareness the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests brought to police violence.

Joseph Williams, director of Students Deserve since 2019, said that after Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police in May 2020, protests broke out at LA City Hall and the District Attorney’s office, demanding the defunding of police at the city and county levels. Though Students Deserve and other advocacy groups had already been pushing for the decriminalization of students of color, the nationwide attention on racial injustice added momentum to their efforts during a period of grief and unrest.

“We started asking, how can we use this energy from these massive protests to win some concrete victories at the school district level?” Williams said.

That’s when Students Deserve and Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles started planning rallies at school district headquarters. Frazier said it wasn’t just students organizing — teachers, parents and community members also gathered in full force. “Every week, we were holding public actions in front of the LAUSD building,” Frazier said “We held public press conferences that were blasted on the news. We were extremely vocal.”

Students Deserve also found strength in partnering with over 70 organizations, including the ACLU of Southern California and the United Teachers Los Angeles union, to form the Police-Free LAUSD Coalition. In June 2020, the coalition led several weekly marches to school board meetings, with hundreds gathering to give public comments. Simultaneously, the coalition led social media campaigns with hashtags like #PoliceFreeLAUSD, #DefundLASPD and #CareNotCops, encouraging community members to tag the superintendent and board members’ social media accounts. An online petition garnered over 17,000 signatures that sent direct emails to elected officials.

Sassou Djato, then a Dorsey High student, said Students Deserve members joined a series of meetings to draft a divestment and reinvestment plan. The proposal, which evolved through over 80 drafts, included detailed input from all the organizations in the coalition and negotiations with the superintendent’s team. Djato remembers confronting board members over Zoom. “We laid out specific timelines of what would happen if the school police weren’t defunded in the near future,” Djato said. “They couldn’t poke any holes in our arguments.”

Of the seven LAUSD board members, four votes were needed for divestment. Because all of the groups had a long history of organizing for education justice, they had different relationships with board members and were able to move them in different ways. “Ultimately, we were able to get four school board members to agree on divesting $25 million,” Williams said. On June 30, 2020, the board passed the divestment proposal as a budget amendment on a 4-3 vote.

Board member Kelly Gonez abstained from voting on a defunding proposal on June 23 but voted for the 35% budget cut a week later, saying student testimonies helped sway her vote. “The experience of students is at the heart of the decisions I make as a board member, and I heard loud and clear from students about the impact of police on their feelings of safety and belonging at school,” she said.

Throughout the campaign, Students Deserve — which is 99% students of color and 70% Black — kept students’ stories at the forefront of their demands. Lakell White, a current senior at Dorsey High School, emphasized how important it was that the movement centered Black students because the district is 8% Black, but Black students made up 25% of the district’s annual arrests and citations in 2017. “There is a huge difference between having students in your organization and actually being student-led like Students Deserve. [Board members] were hearing straight from people who go to the schools,” White said. “The magic of Students Deserve is that it’s led by Black students.”

Though Djato graduated before being able to see the effects of the implementation, they said the point of their organizing was to help future students feel safe on campus. “The fact that they get the benefits is more than enough,” Djato said. “That, right there, is success to me.”

The impact of defunding school police

Since 2021, the Black Student Achievement Plan’s budget has grown from $37 million to $135 million, with the constant advocacy and monitoring of results by groups like Students Deserve. With the program’s additional funding, schools have been able to hire more psychiatric social workers, restorative justice coordinators, attendance counselors, school climate coaches and ethnic studies instructors. Students are offered mental health sessions, college counseling and early-conflict intervention to help with their socio-emotional growth. A 2022 survey of 2,300 students in schools with the program found that 87% of Black students felt like they had benefited from its implementation. A 2023 report showed academic gains for Black students: an 8% increase in graduation rates, a 7% increase in literacy rates, 3% increase in AP course enrollment and a 12% increase in attendance.

Sikivu Hutchison, the parent of a 10th grader at Hamilton High, praised the program for providing many resources that hadn’t existed. “We now have dedicated professionals that are there to provide mental health services. Students are getting academic enrichment and college prep, and BIPOC students can go on college campus visits,” she said.

Butler-Thomas has directly reaped some of these rewards. In her junior year, she was able to tour HBCUs in Atlanta through a field trip sponsored by the program. “That was my first time stepping foot on a college campus and being able to picture myself there. Without BSAP, I never would have been able to firsthand see what a college environment is like,” she said.

For Black and Latino students who come from communities that bore the brunt of the pandemic’s death toll, psychiatric social workers have been an important on-campus support system. “I lost my Dad to COVID-19, so I go to them for help,” White said. “There’s still a mental health crisis from the pandemic, because a lot of us lost our parents and caregivers.”

While there is a lack of data on the relationship between school district police divestment and school violence, a 2023 analysis of publicly available LAPD data noted that reports of crime on district campuses were down from 2019 pre-pandemic numbers. However, the report notes the decline could also be from a post-2020 cultural shift — people, including school administrators, are now more careful about when to call police.

For their part, school police have seemed to accept their removal. A spokesperson for the LA School Police Department said the department has “embraced the opportunity to reassess our practices and explore alternative strategies to maintain school safety while promoting positive relationships between law enforcement and the school community we serve.”

As for the Students Deserve activists, many described the empowerment that came from telling their stories on a public platform. When Butler-Thomas took the stage to represent Students Deserve at a strike for the United Teachers Los Angeles union in 2023, she found herself speaking in front of 40,000 people. “I used to be very shy. But being out there in the rain with my teachers — it was beautiful,” she said.

Frazier says she’s most proud of discovering who she was and finding her voice through her involvement in Students Deserve. As a current freshman at UCLA, she is conducting academic research on the school-to-prison pipeline. She dreams of becoming a juvenile attorney and working with youth in communities of color. “One day, everything that we’re fighting for, it’s going to be a part of history,” she said.

Turner called the empowerment that the activists in Students Deserve experience “transformative agency,” explaining that once students work collectively to combat institutions, they discover that they have the power to change them. “Young people are learning civic processes and how public policy works. They also learn to negotiate with power brokers, advocate for themselves and build relationships,” he said. “Once they’ve built these skills, they’re able to movement-build and bring others into the movement.”

The challenges ahead

The activism of Students Deserve members hasn’t always been met with approval. Frazier said students faced constant backlash, sometimes even from within their own community. “A lot of teachers didn’t agree with defunding the school police. That was hard because I had so much respect for them. A teacher at my school was interviewed for an article where he rebutted everything we said,” Frazier said. Eventually, she had to make peace with the fact that not everyone was going to agree with her beliefs.

Frazier also explained that it could feel overwhelming for students to juggle their personal lives with schoolwork and organizing. “I just kept going and going, and I felt like at some point, I lost that flame that really set my soul on fire. I was really burnt out, and I had to step away from activism work for a while. It was hard to explain why to others,” Frazier said. Djato echoed Frazier’s statements about the stress of organizing during the global pandemic. “It definitely took a physical and mental toll on me,” they said.

The student activists recognize that their work is ongoing. The LA school police budget remains funded at $58.5 million a year — with money going to patrolling neighborhoods, traffic safety and parking enforcement — and the Students Deserve’s goal is the complete elimination of the LA School Police Department. Students Deserve has also mobilized around what members believe is a lack of commitment by the school board to community-based safety programs. Though $15 million annually was earmarked by the board in 2021 for such programs, most of the money has not been spent.

One community-based safety initiative, called Safe Passage, would hire and train trusted community members to accompany students to and from school on “safe routes.” The board unanimously passed a resolution in June to analyze the landscape of community-based safety solutions, but Students Deserve members said the board has missed deadlines and has yet to produce the required reports.

“One time, I was chased after getting off the train on my way home from school,” Butler-Thomas said. “I brought that story with me to the board to ask for Safe Passage. They don’t seem to be listening to us.”

When asked about the status of community-based safety programs, School Board President Jackie Goldberg’s office said “school safety and student achievement remain high priorities across the district.” Board member Gonez said “change hasn’t come fast enough,” but she didn’t elaborate on what was holding up the reports. “Our students are navigating trauma from the pandemic, community violence, and gang activity,” she said. “Ensuring school safety means addressing those mental and physical safety needs before violence occurs – and that takes investing in community-based solutions.”

White said she will continue to press for the Black Student Achievement Plan and community-based safety measures because she grew up in a family that was directly impacted by the school-to-prison pipeline. “My dad and my two brothers all spent time in jail. I’m a first-generation high school graduate and will be a first generation college student,” White said. “Oftentimes, LAUSD programs for Black and brown students come and go. We want to make sure that BSAP and community-based safety is here to stay for good.”