DeNeen Brown spent years researching origins of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, in which as many as 300 Black people died during a riot orchestrated by a mob of white supremacists in Oklahoma.

What she discovered was startling. According to her research, the riots, which also led to widespread destruction of the the area known as “Black Wall Street,” started with one racially inflammatory headline on the front page of the Tulsa Tribune: “Nab Negro for attacking girl in elevator.”

“That headline sparks this massacre,” said Brown, associate professor at the University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism. “More than 1,200 Black homes and businesses were destroyed. Ten thousand Black people are left without their homes. The whole area of Greenwood, this thriving Black community… is destroyed because of the headline.

“How many other headlines are out there in history that we don’t really know about, that prompted lynchings and massacres,” she added.

This revelation led Brown, also a Washington Post writer, to launch Printing Hate, a yearlong investigation into the ways newspapers contributed to racist violence in the United States from Reconstruction to Jim Crow.

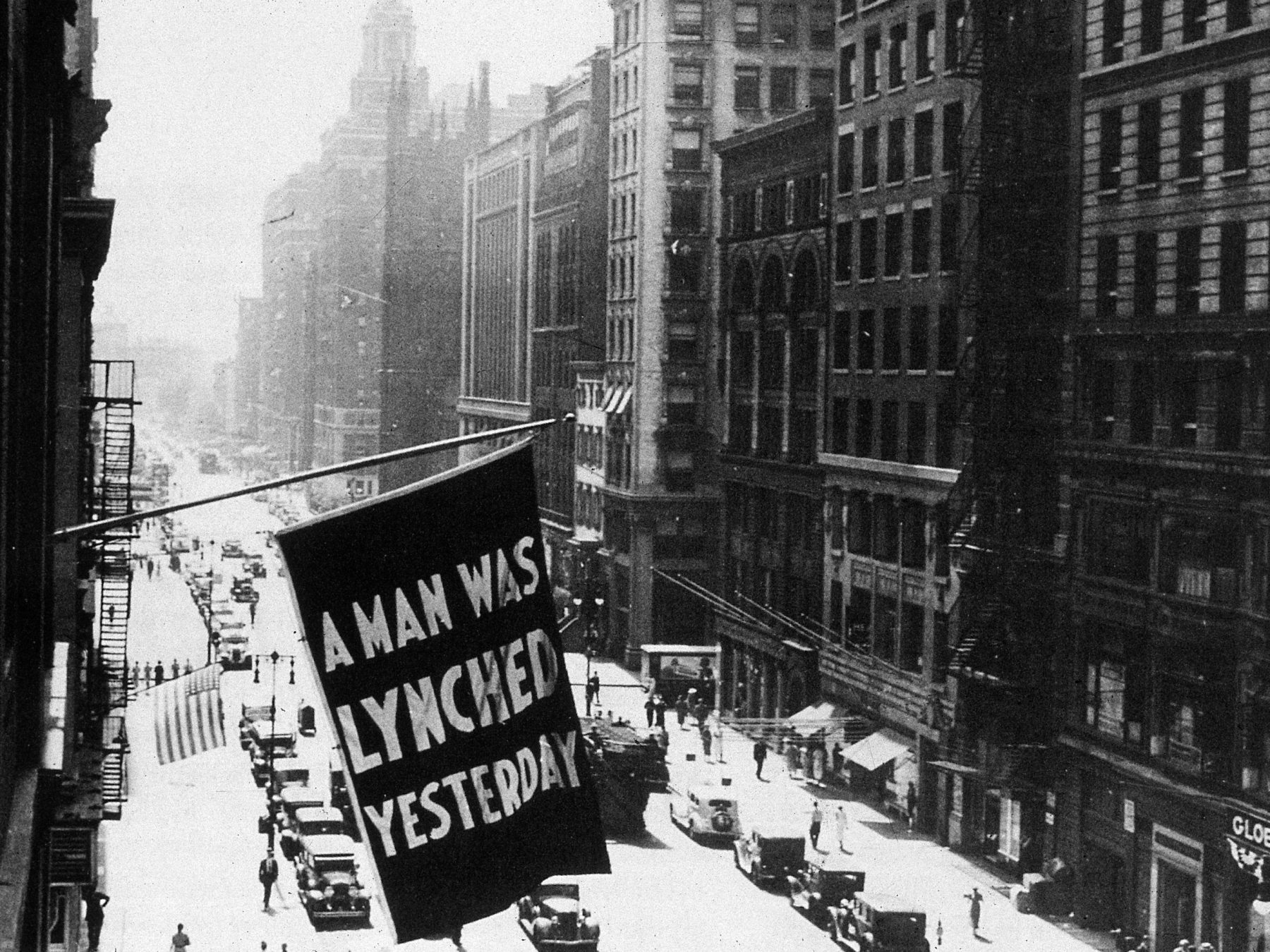

“The Black Lives Matter protests that drew millions to the streets over the last two years pushed many communities and businesses in the U.S. to reckon with their racist pasts. But one industry — with a few notable exceptions — has largely been silent. Newspapers,” the project’s website says. “From the end of Reconstruction to 1940, newspapers were the most powerful news medium in America. Those run by white supremacist publishers and editors printed headlines and stories that fueled racial hate, inciting massacres and lynchings of Black citizens.”

The project will include more than 30 stories, published Mondays and Thursdays until mid-December, as well as an app that allows readers to explore how 100 newspapers covered lynchings at the time. Some of the stories already released include:

- “Massive public lynchings of Black men were nurtured by Waco, Texas, newspapers”

- “Yazoo City’s newspaper had a history of providing a forum for its pro-lynching readership”

- “Kentucky newspapers often blamed Black victims for lynchings”

- “Newspapers dehumanized Black victims of lynchings in Tallahassee by describing them as animals or insane”

Led by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, students from colleges such as the University of Maryland, Hampton University, Howard University, Morehouse College, Morgan State University and North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University also contributed to the project. (Hampton University, Morgan State University and North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University are academic partner schools of NBCU Academy.)

Students examined lynching coverage from 1865-1965 in digital newspaper archives, data and audio recordings, and also interviewed descendants and historians about the impact white-owned newspapers had on Black communities at the time.

Milton Coleman, a retired senior editor at the Washington Post and a visiting professor at Howard University, also contributed to the project and said the work gave students valuable tools to succeed in the newsroom “in ways they would not ordinarily get.”

Coleman said there was also a broader mission which involved the two Howard University students that Coleman brought to the project.

“I wanted the students, both Black women, to be exposed to DeNeen, a Black woman,” he said. “I want them to see how successful journalists look just like them, Black women who have proven that they are really, really good journalists.”

Jackie Jones, dean of the School of Global Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University, said that while students were enriched by the project, it may cause some of them to reevaluate their place in the industry.

“You can’t walk away from a story like that,” Jones said. “Just to see the complicity of the media. And I have to say, none of the students have voiced this to me, but I have to imagine that they must feel some kind of way when you’re thinking about going into a business that was party to something that hurt your people.”

“How many other headlines are out there in history that we don’t really know about, that prompted lynchings and massacres.”

— DeNeen Brown, University of Maryland’s Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

For Brown, it’s been a painful reporting process that’s had a “profound impact” on everyone involved.

“I’m angry. I’m sad,” Brown said. “I’m the mother of a Black young man. I’m a sister, daughter, aunt. And I’m just so emotionally wrenched.”

However painful it’s been for her to report on, Brown said the work is critical — and people need to know this history.

“A lot of people don’t know this history, they don’t know the role of newspapers. People are just aghast that a newspaper would print a headline like, ‘Negro fiend to be lynched at five o’clock this afternoon,’” she said.

“People don’t know how newspapers portrayed Black people, and how that fed the racism in those communities, how it destroyed lives, how, as a result, some Black communities were wiped out. So I think it’s a powerful, powerful package.”