When it comes to stories about race and racism in the U.S., the public often prefers what Harvard University assistant professor Brandon Terry calls “romantic narratives.” This couldn’t be truer than when it comes to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

More than 50 years after King’s assassination, coverage of the civil rights leader is often relegated to “a story about unity that’s woven into a broader imagination of Americans coming together to transcend the original sin of racial domination,” said Terry, who teaches African and African American studies.

While that’s an enticing story, it’s ultimately untrue. Americans have not achieved King’s dream of racial and economic justice. In fact, he would likely weep if he saw our current world. He stood against racism, poverty, war and violence — all evils that still have a chokehold on our society.

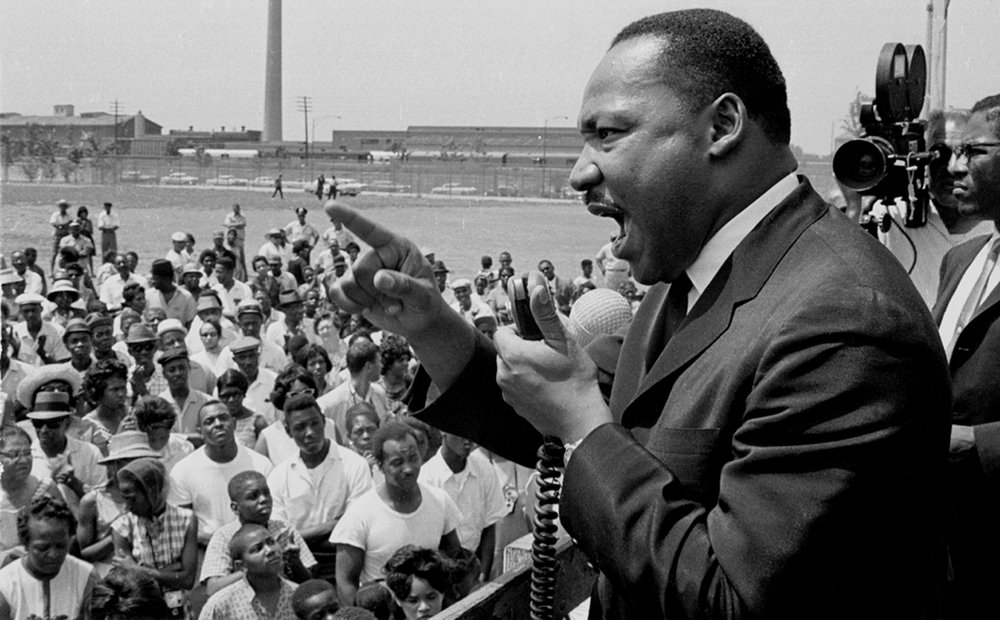

King knew that racial justice wasn’t a problem to be fixed in a generation. His ideas were also radical for his time. He gave impassioned speeches against white supremacy, capitalism and imperialism — specifically, opposition to the Vietnam War. “The price that America must pay for the continued oppression of the Negro and other minority groups is the price of its own destruction,” King once said. He was an inspiring figure, but he was far from relaxed about injustice.

Lerone Martin, director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, says journalists must avoid falling into simplified narratives of King or using them to prop up America’s greatness. It was the United States government, after all — particularly J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI — that remained fiercely opposed to King and his mission.

“The American public largely found him to be a nuisance,” Martin said. “Many people, white and Black both, felt that everywhere he went, there was violence, even though he was a nonviolent protester. And of course, the American state surveilled him, monitored him and eventually Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.”

It’s the media’s job to convey King’s whole legacy — nonviolent and radical, revered now and regarded with distrust in the past (and currently by some conservatives). This means including the context surrounding his work and how his life is celebrated. Here is how journalists can do that better.

Root your articles in history

King was deeply interested in history. Terry says journalists should push themselves to ground their work in historical analysis, just as King did. “Dr. King was always making historical arguments, moving the whole history of Black politics from Frederick Douglass to W.E.B. Dubois to Marcus Garvey, so that people can understand all the things we tried before we got to nonviolent direct action,” Terry said. “He was always trying to tell a richer historical narrative — and that matters when you’re trying to understand structural injustice.”

Terry gives an example of how journalists can use history to cover news about race and racism, on Martin Luther King Day and beyond. The easier path is to cover disagreements and “controversies” over issues of race. But the intellectually curious and responsible journalist should “situate that in a broader history,” Terry said. This can apply to topics like critical race theory in school curriculums, Islamophobia directed at Black Muslims in the U.S., and colorism in the entertainment industry.

Then there is the historical context of Martin Luther King Day itself. Martin points out that we rarely acknowledge that the president who signed off on the holiday, Ronald Reagan, was reluctant to do so. He is also partially responsible for the watered-down version of King we see in the media today.

“In order for Reagan to sign the bill making it a federal holiday, Dr. King’s image had to be anesthetized in some way,” he said. “In the signing ceremony, Reagan really pared down King’s legacy by simply saying Martin Luther King Jr. believed in the American dream and making sure that everyone could share in the American Dream. He completely removed King from his critique of American policy around war, poverty and the social safety net, and the role of racism in the country.”

Acknowledge King’s radical political philosophy

Terry has a simple suggestion for journalists who don’t want to obscure King’s radical legacy. “Part of what it means to really understand the radical King is to read him,” he said. “He wrote so extensively and he articulated a real vision of political philosophy. We have to immerse ourselves within it to understand what his radicalism consisted of.”

Terry says if you sit with King’s ideas for a while, “you really get a sense of his mind and what he was after. Why did King think the right to vote was so tied up with human dignity? The answer is really interesting. Why does none of the media coverage of him really wrestle with that?”

Journalists shouldn’t just include King’s books on reading lists; they should read them themselves. Works like “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story” (1958), “The Measure of a Man” (1959), “Strength to Love” (1963), “Why We Can’t Wait” (1964), “Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?” (1967) and “The Trumpet of Conscience” (1968) will expand your understanding of King’s political philosophy, making it easier to communicate that to readers. Same goes for reading or listening to his speeches in their entirety, not just watching snippets on YouTube. King wasn’t just someone who wanted racist comments in interpersonal relationships to stop, although he certainly cared about that. King was someone who wanted to transform an entire system, who saw clearly the links between racism, classism and imperialism.

“He gave a really important speech about poverty here at Stanford University in 1967 called ‘The Other America,’ where he talked about how there was one America where the land is filled with milk and honey, and there’s another America that’s filled with rodents and empty stomachs and people who were unhoused,” Martin said. “One of the solutions he put forward for that was the consideration of a universal basic income, something that’s still being talked about today.”

King also said poverty was as backwards as cannibalism, Terry said. It was King’s fervent belief that as America remained enmeshed in the glorification of white supremacy and the edification of capitalism, it would become an increasingly irrational and unstable society, wreaking havoc within its own borders and all over the world.

It’s this kind of prescient analysis that King should be more regarded for.

Avoid the extremes of blind optimism and nihilism

It’s not that King’s words and perspectives should be seen as proof that all hope is lost and there is no point in trying to change the world. With King, you can hold the darkness and the light.

“It’s very hard for us to try to figure out how we can lift up and celebrate and take accurate stock of the genuine victories of our civil rights figures like Dr. King, while not treating those victories as sufficient or treating their failure as reasons for profound nihilism and despair,” said Terry.

Even though it’s true that we haven’t reached the world King envisioned, despair was also not a value he held dear. He believed that while the fight against inequality was eternal, it was of the utmost importance to fight.

The media can sometimes portray social movements like wars, with a start and end date. But King’s struggle didn’t end with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It didn’t end when we got a Black president. For that matter, it didn’t begin with King. It began when Black people arrived in the Americas after being stolen from our homelands, and in many ways, it began long before that, when the Indigenous people in the Americas were colonized by Europeans.

King does not represent who America has always been, but he does represent what this fight has always been about — dignity, respect and love. Much like we cannot talk about his nonviolence without talking about his radicalism, we cannot discuss his radicalism without discussing the love he had for his people, the passion he had for the dignity of all human beings, and how that motivated him to keep fighting.

Editor’s Note: The word Negro is a dated term used to describe African-Americans and is now considered offensive.