An American citizen voting — surely there is nothing remarkable, let alone sinister, about that. Yet, if you’re an African American or other person of color, voting — for most of the 20th century and now the 21st — has proven to be a difficult, often impossible act.

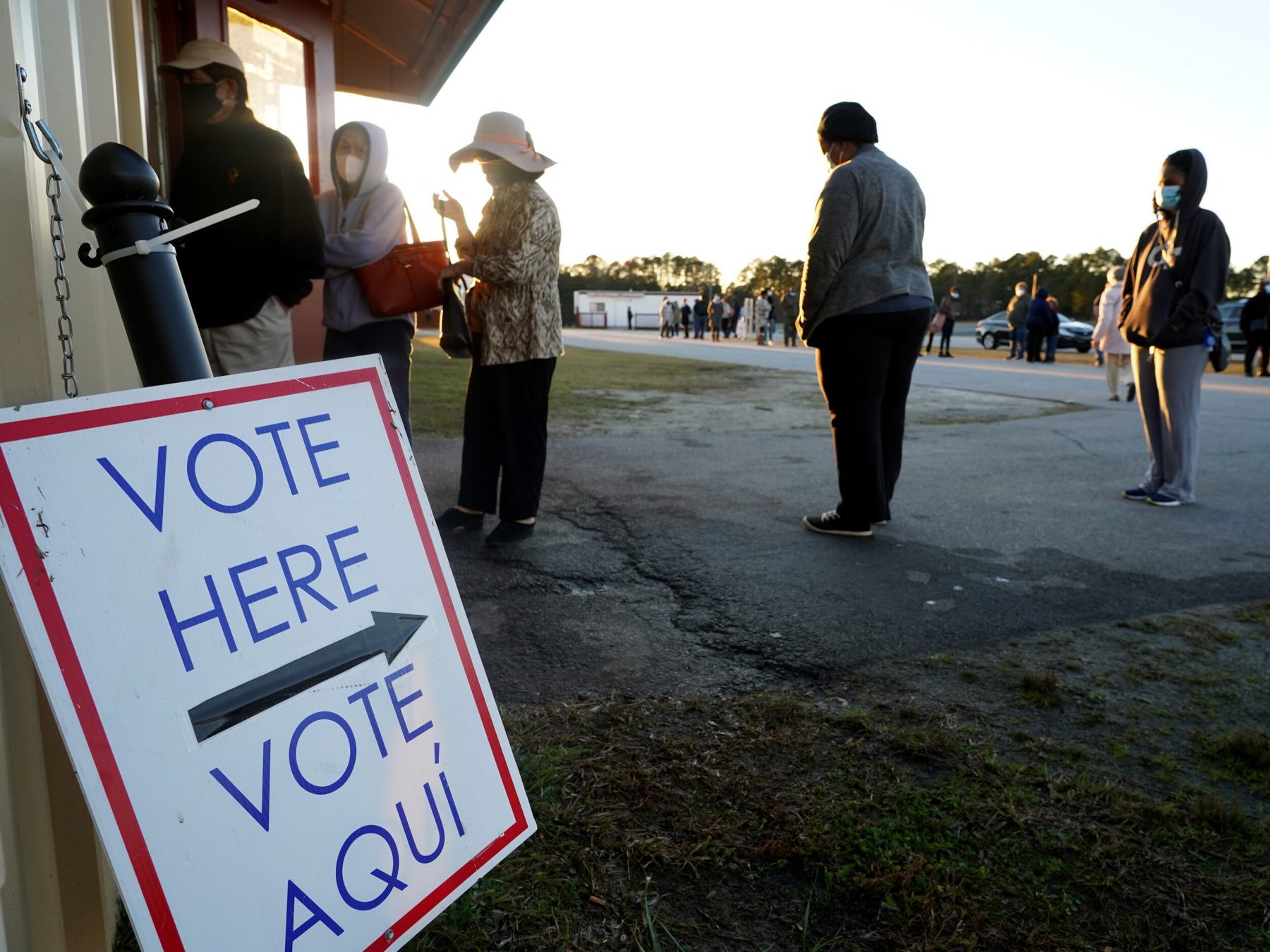

Voting rights have been making headlines this year, particularly after the Georgia state Legislature passed and Gov. Brian Kemp hurriedly signed into law legislation that prevents many Black citizens from voting. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed his new bill into law in a ceremony televised on Fox News. Texas legislators will soon vote to criminalize once normal voting procedures — such as making it a crime to send unsolicited applications for mail-in ballots to potential voters. As of late March, 47 states have introduced 361 similar bills — a 43 percent increase in bills from the previous month.

These laws include a limit to “no excuse” absentee voting, an end to Sunday voting — especially popular among African Americans — limits on the number of drop boxes for mail ballots, stricter voter identification requirements for absentee ballots and making it illegal to provide food and water to those waiting in line to vote.

Biden is wrong when he declares that voter suppression is “Un-American.” In fact, it’s as American as cherry pie.

Supporters of this legislation are overwhelmingly Republican and claim that these laws are necessary to prevent what they claim is the widespread voter fraud that occurred during the 2020 presidential election — even though there is no evidence to prove that such fraud took place. President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has called Georgia’s new law “sick” and “un-American,” with other critics insisting that the new laws are classic examples of the voter suppression that prevented African Americans from voting for most of the 20th century before the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

But for reporters covering these new laws, it’s important to not just view them as a debate between two political parties — but also through the lens of history. As a scholar who has written about the history of American voting, I urge journalists to look back to understand the present. As William Faulkner reminds us, “History isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” The history of African American voting, one of retreat more often than advance, suggests that President Biden is wrong when he declares that voter suppression is “Un-American.”

In fact, it’s as American as cherry pie.

“A hollow, unpractical idea”

The struggle over voting rights goes back more than 150 years.

Before Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, only five states — all in New England — allowed Black men to vote. When New York first permitted Black men to vote, it required that they own property. In the South, almost all Black people were considered property and, as slaves, were prohibited from voting.

Lincoln’s Democratic successor, Andrew Johnson, called Black suffrage “a hollow, unpractical idea.”

Not even the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 initially led to Black voting. Lincoln’s Democratic successor, Andrew Johnson, called Black suffrage “a hollow, unpractical idea” which would “cause great injury to the white and colored man.”

But Republicans in Congress, during the period later known as “Radical Reconstruction,” opposed Johnson and passed a series of laws and constitutional amendments that eventually gave Black men the right to vote. The 14th Amendment was passed in 1866, providing Black people citizenship and legal equality, but not the right to vote. The Reconstruction Act, passed over Johnson’s veto, divided the South into military districts occupied by federal troops and prohibited the former Confederate states from returning to the Union until they ratified the new amendment.

The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, prohibited the federal or state governments from denying any American’s voting rights “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” granting a generation of Black men — many of them former slaves — the right to vote and the chance to win political office. (Women would not receive that right until the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.)

Literacy tests and poll taxes

Radical Reconstruction brought Southern Blacks political freedom, leading to as many as 2,000 Black state legislators, city councilmen, tax assessors, justices of the peace, jurors, sheriffs, and U.S. Marshals. Fourteen Black politicians also became U.S. congressmen, and two became senators. But the new era of Black activism did not last long.

Northern support declined; a conservative Supreme Court abolished laws designed to assist Black citizens; and terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the White Camellia destroyed Black schools and churches and murdered at will.

“At first we used to kill them to keep them from voting,” one Alabamian said at the time. “When we got sick of doing that, we began to steal their ballots.”

By 1877, Southern white Democrats had overthrown every new state government and established state constitutions that stripped Black citizens of their political rights. To circumvent the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, legislators created clever devices that would disenfranchise Black citizens for the next 80 years.

These included literacy and “understanding” tests; poll taxes; residency and property requirements; and a “grandfather clause” that exempted white men and their male descendants from such criteria if they had voted prior to January 1, 1867 — three years before the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteed Black citizens that right. Later, the all-white Democratic Party primary barred Black candidates.

The new laws gave the greatest power to local registrars, who would choose which applicant succeeded or failed. The intent of the laws was explicit: “The plan,” said one Mississippi official in 1890, “is to invest permanently the powers of government in the hands of the people who ought to have them — the white people.”

The laws were disastrous for newly empowered Black citizens. In Louisiana, 130,000 were registered to vote in 1896. By 1904, only 1,342 remained to exercise the franchise, if whites permitted it.

“At first we used to kill them to keep them from voting,” declared one Alabamian; “when we got sick of doing that, we began to steal their ballots; and when stealing their ballots began troubling our consciences, we decided to handle the matter legally, fixing it so they couldn’t vote.” By the early 20th century, Black disenfranchisement, like economic and social segregation, was complete throughout the South, and it remained almost unchanged for the next 60 years, until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

A “mighty surge” of Black voters

For Black Americans, the Voting Rights Act was nothing short of revolutionary.

For decades, when they went to register to vote they faced hostile, insulting and all-powerful registrars. Often, they had been warned to not even try. Mississippi Senator Theodore Bilbo feared “a mighty surge” of Black voters and encouraged “red-blooded men to do something about it.” They often did. When a veteran and his wife went to the polls in Gulfport, Mississippi in 1946, a group of white men stopped them, then began beating and dragging them from the building. One Mississippi minister who encouraged his parishioners to vote was shotgunned to death by white men who were never caught or punished.

The registrar could ask them anything and often did: “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?”

If they were fortunate enough to enter the building and allowed to stay, they were forced to fill out a questionnaire, and if they made even the most minor error, they were rejected. They were also tested orally on the state and federal constitutions as well as confronted with questions so complicated that law professors couldn’t answer them. The registrar could ask them anything and often did: “How many bubbles are in a bar of soap?” Shown a jar filled with jellybeans, they were required to guess how many it held. The Voting Rights Act eliminated those tests.

The Voting Rights Act replaced the registrar with the “federal examiner” who would police elections in those counties where it was obvious that Black voters were historically discriminated against. Interfering with voting was now a federal crime, carrying a penalty of five years in prison and a $5,000 fine.

The Voting Rights Act was truly bipartisan. Many Republicans played a key role in creating and then later defending it.

After the applicant completed the process, they received a certificate noting that they were now registered to vote. It was an extraordinary moment because the examiners addressed them politely as Mr. or Mrs., probably the first time in their adult lives that they had been given that particular form of respect.

At first, the Voting Rights Act was truly bipartisan.

Many Republicans played a key role in creating and then later defending it, including Republican Minority Leader Senator Everett Dirksen, who joined with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s lawyers to craft a bill that would bring Republicans along. Ninety-two percent of Senate Republicans supported its passage, more than Senate Democrats. When temporary provisions came up for renewal, Republican Presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan, and George W. Bush signed the bill into law, even though some of their new constituents in the South opposed it.

Each renewal brought changes that enlarged the franchise. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18; English-language ballots became bilingual.

The Voting Rights Act had liberated African Americans, especially in the South, from the legal constraints that had previously prevented them from voting, and members of the U.S. House and Senate, including Republicans, sought their votes.

In 2006, every member of the U.S. Senate voted for renewal of the Voting Rights Act.

The Obama coalition

The Voting Rights Act helped elect the country’s first African American president in 2008. But the coalition President Barack Obama built persuaded Republicans that they should abandon their support for Black voters. The only way they could win the presidency, they concluded, was through voter suppression.

Following the Republican congressional victory in 2010 — which led to Republican control of both legislative bodies in 26 states, and 26 governorships — Republican legislatures passed and governors enacted a series of laws designed to make voting more difficult for Obama’s constituency — minorities; the poor; students; and the elderly or handicapped.

The coalition Obama built persuaded Republicans [to] abandon their support for Black voters.

They anticipated what was to come in 2021, including the creation of voter photo ID laws, measures affecting registration and early voting, and, in Iowa and Florida, laws to prevent ex-felons from exercising their franchise. Then, in 2013, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority struck down the crucial “pre-clearance” provision that gives of the Voting Rights Act its power by requiring states and counties with a history of discrimination to get federal approval before making any changes to existing voting laws.

Once again, the voting rights of American minorities were in peril. They remained so under President Donald Trump and they continue to be imperiled today.

Democrats have offered two bills to combat these efforts and enlarge ballot box access — but both appear unlikely to pass because of Republican opposition in the Senate.

The first, the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act, named for the late civil rights activist and Georgia congressman, passed the House in 2020. It would fix the “pre-clearance” formula the Supreme Court struck down in 2013. The second, “For the People Act,” has been called a “sweeping democracy reform bill.” It would create automatic voter registration, expand mail voting in every state and take on structural issues such as gerrymandering and public financing of congressional elections.

“The struggle of a lifetime”

How do the new voter suppression laws compare with the those that were created before the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965? Race, gender and property determined who could vote in America’s earliest elections. Today, it’s party affiliation. Republicans clearly support laws that limit the right to vote while Democrats seek to create ones that enlarge the suffrage.

Journalist Ari Berman, an expert on voting rights, calls the current struggle the “GOP’s war on democracy and voting rights,” and there is evidence to support this assertion. The bills were written by Republican state legislators — often with the help of Republican groups like Heritage Action for America — and signed into law by Republican governors. Many continue to support former President Donald Trump and believe that he was unfairly robbed of his office.

No one felt the attack on voting rights more intensely than John Lewis. Shortly before his death last year, he reminded Americans that “our struggle is the struggle of a lifetime. We must never go back.”