“I really wasn’t too keen on therapy, because I always felt like therapy was for individuals who were mentally ill.”

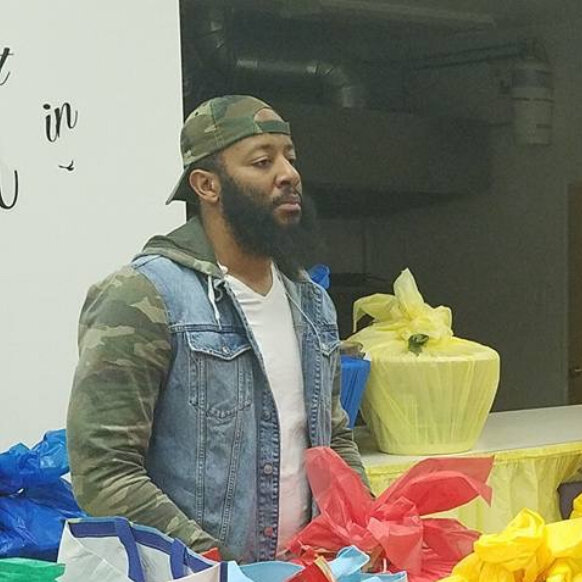

This is what Ajene Prince believed raised in a neighborhood where violence felt like the norm and men were expected to be tough. Then 2020 happened.

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, and the worldwide protests that erupted over the police violence inflicted on Black Americans, Prince, then 33, was looking for a space to express his emotions freely. The heaviness of the moment weighed on him, resurfacing the grief he had experienced losing numerous friends to violence as a teenager.

He reached out to his college fraternity brothers, and one of them posed a question in their group chat: Where do they go when they feel they have no one to talk to? One member shared a link to Black Men Heal.

That year suicide was the third-leading cause of death for Black people ages 15 to 24 in the U.S., with Black men being four times more likely to die by suicide than Black women. According to a Harvard Medical School study, only 25% of African Americans seek mental health treatment, compared with the 40% of white Americans who do. Poor health care access, financial barriers, a cultural stigma around mental health and a history of medical distrust all contribute to these disparities. Black Men Heal is one of a handful of nonprofits helping Black men overcome these hurdles by offering them free treatment, education and resources, pairing them with therapists they can trust.“

“Black men aren’t the first ones knocking down your door to willingly come to individual therapy,” said Edie King, lead clinician at Black Men Heal. “And I think a lot of it has to do with how they are socialized and the lack of emotional privilege that they have in terms of being able to have safe spaces and access, even understanding emotional intelligence.”

Founded in 2018 by five therapist friends who recognized a mental health gap in their Philadelphia community, Black Men Heal has facilitated over 3,500 free therapy sessions for Black men nationwide. More than 70% of its clients opt to continue therapy after the free sessions are over.

“[When] I was researching different therapists, it was a money issue or trying to find that natural connection,” said Prince. “It’s hard for Black men to rely on therapy when there’s not a lot of Black men who are therapists.”

Coping with a history of violence and trauma

Prince was born and raised in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia, a city known for its high crime rates and gun violence. In 2022, one in every 67 Black men ages 18 to 24 in the city were killed or injured in homicides or shootings.

“I watched my best friend get killed in front of me, I watched a couple of other people get killed in front of me, too,” Prince said. “So, it almost felt like a numbing feeling, but you started getting used to death. Death is never an easy pill to swallow.”

From June 2005 to August 2006, Prince attended 33 funerals. In a culture that valued male strength and viewed sadness as a sign of weakness, allowing himself time to grieve was not an option. It wasn’t until his first therapy session with Black Men Heal, 14 years later, that he recognized he had been grappling with depression.

A 2016 review of Black trauma survivor studies found that exposure to trauma, whether through witnessing violence or being directly victimized, is a daily reality for many Black boys and men. But they aren’t always taught how to cope, or given the tools to do so. The same study found that 56% to 74% of Black men who have faced traumatic events may have an unmet need for mental health services.

Black Men Heal launched its gun violence group therapy program in 2022, in partnership with the city of Philadelphia, to offer resources and therapy to teens and adults in some of the city’s most vulnerable neighborhoods. Last year, the group held over two dozen sessions at high schools and community gatherings.

“Our focus is helping individuals to understand more about how gun violence impacts their mental health, and helping to increase their awareness about alternative solutions to dealing with the grief,” said King. “Ultimately, [the goal is] to help decrease the likelihood of retaliation because what we understand and what studies show is that most gun violence, especially in urban neighborhoods, is retaliation.”

Fighting the stigma against therapy

In recent years, there has been a movement to prioritize mental health in communities of color. In Philadelphia, Men Who Care of Germantown Inc. is also helping at-risk youth cope with gun violence, providing scholarship and mentorship opportunities to keep them off the streets. Meanwhile, groups like Melanin and Mental Health aim to increase the representation of clinicians and therapists of color in the industry while encouraging communities to seek mental health support.

At Black Men Heal, one of its most successful services is the eight free individual psychotherapy sessions it offers to anyone who fills out an online questionnaire. The Black Men Heal team then assesses their needs and matches them with appropriate clinicians, often those who share similar backgrounds. But these pairings can prove challenging — according to a 2022 American Psychology Association study, only 4% of the U.S. psychology workforce identify as Black, and of these Black psychologists, only 8% are men.

“I use this concept almost like a dating site, like Match.com — what I recognize is, regardless of what somebody’s therapeutic modality is, that the most effective outcomes in therapy are reached when the relationship between the clinician and the client is high,” said Tasnim Sulaiman, licensed professional counselor and founder of Black Men Heal.

Black Men Heal also offers a “King’s Corner” virtual meetup group, where counselors facilitate open dialogue about topics like fatherhood, stress, anger management and self-care. Another virtual program, Heal With Him, offers a space for women and their partners seeking relationship counseling.

While their programs have been well received, said King, one of the barriers that remains is generational resistance to seeking mental health help.

“One thing that I would say is that with younger Black men I noticed there is a lot more willingness to seek out therapy,” said King. “There’s a lot more willingness to talk about emotions and to express emotions. There is an upcoming generation challenging toxic masculinity.”

But with older generations, that mental health stigma is still hard to shake, she said.

“We reframe this idea that vulnerability is weakness,” said Sulaiman. “We have one of our shirts that says, ‘Vulnerability Is the New Sexy.’”

Encouraging a culture of mental health support

Engaging with communities through on-the-ground efforts, such as collaborating with local nonprofits and hosting discussions on school campuses and at community centers, enables the group to establish trust and foster connections in vulnerable neighborhoods.

“Having groups of people who look like them, who have shared experiences, they then want to apply for the individual therapy,” said Sulaiman.

Over the past six years, the group has expanded to cities like Washington and states like New Jersey and Georgia. Next, Black Men Heal is hoping to create re-entry programs for the formerly incarcerated, empowering men as they transition back into community life.

Black Men Heal operates through volunteer work — most of their licensed counselors donate their time — as well as public donations and grants, something Sulaiman says can be challenging. “In order for us to keep it going, we do need sustainable funding.”

In the meantime, the group continues to help and inspire others. After three years in therapy, Prince decided he wanted to give back to his community. Today, he is pursuing a master’s degree in clinical mental health at Walden University.

“I love everything that I’m learning,” said Prince. “I’m learning about something that has a purpose in life and that’s going to be my purpose.”

Prince said his ultimate goal is to secure his therapist license and work in Philly, his hometown. “I have to cater to my community first,” he said, “and I know there’s a lot of people there just like me.”