The first time Sophie Sandberg remembers being catcalled, she was 12. She was walking down the streets of New York with her friends and heard men three times her age holler sexually explicit things at her.

“I was this happy teenager wearing bright, colorful dresses and expressing myself, and then when the catcalling started, suddenly there was this shift, and I would go outside and I felt like the attention was all on me,” said Sandberg, now 27. “I felt so self-conscious.”

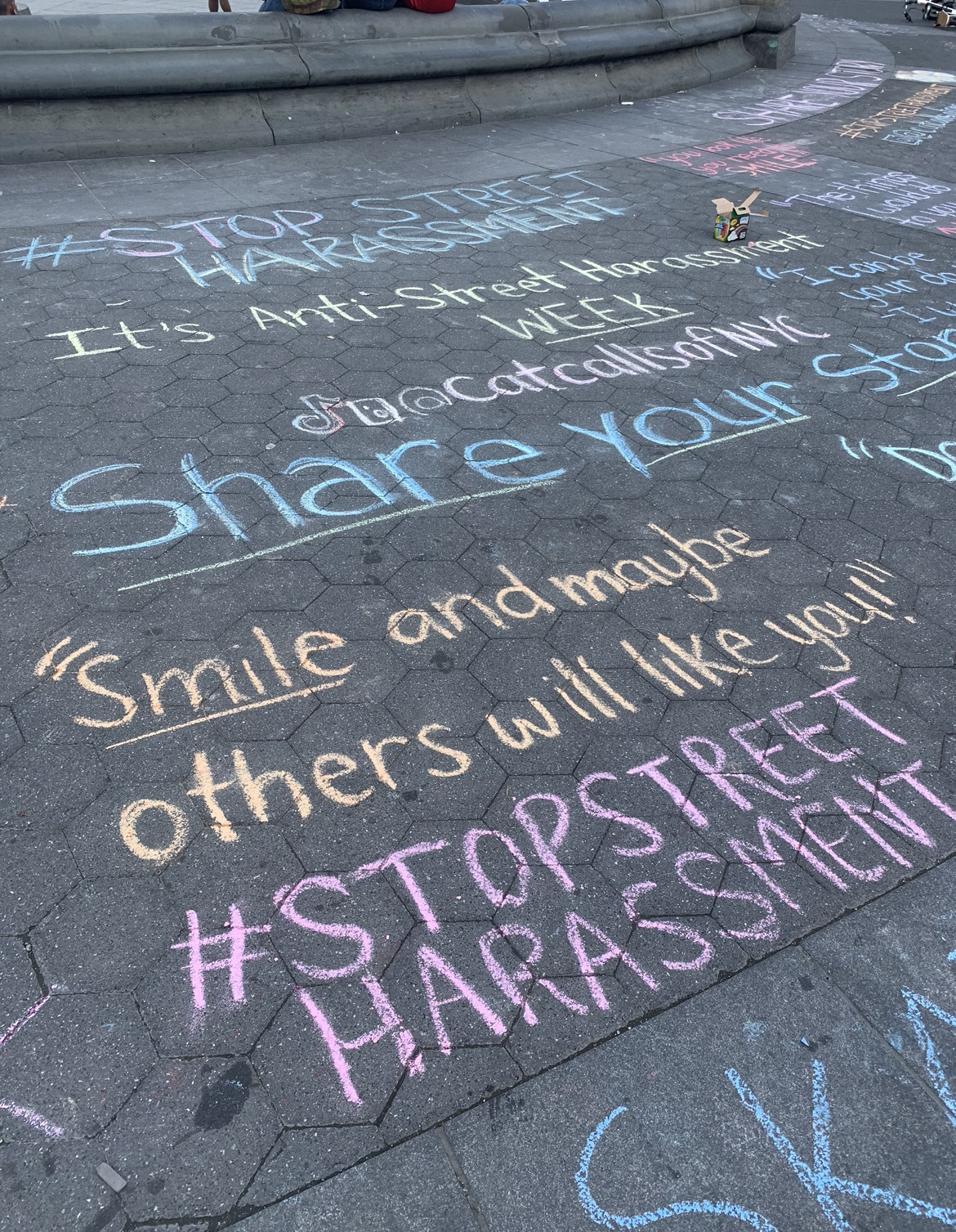

Sometimes she’d hear up to five catcalls every day while walking around the city. Men would call her “baby” and tell her she had “sexy legs.” She grew sick of the unwanted sexual comments and noises, so at 19, she decided to “chalk back.” With bright, pastel-colored chalk, she began writing phrases that had been hollered at women on city sidewalks, to bring awareness to — and hopefully curb — street harassment.

“The colors really stop people, and the jarring contrast is almost kind of similar to being catcalled,” she said. “It draws people in and makes them pay attention to this problem.”

Over the past eight years, her Catcalls of NYC initiative has become an international movement called Chalk Back, with more than 1,000 activists participating around the world. The mission is to create conversation, provide a platform for sharing personal stories of sexual harassment and promote cultural change through art.

The organization asks women, queer and nonbinary people to submit the catcalls they’ve heard, and then the activists will chalk the catcall at the same location where it occurred, either alone or as a group.

“I wanted to do something that was about uplifting the voices of those who are experiencing catcalling, creating community and dialogue about the issue,” Sandberg said. “The goal was to bring it to a public space.”

More than 80% of women have experienced some form of sexual harassment in their lifetime, according to a survey from the nonprofit Stop Street Harassment taken during the height of the #MeToo movement in 2018. About 66% of those women said they’d been sexually harassed in public spaces. The survey also found that more than half of women have experienced sexual harassment or assault by age 17.

Sandberg believes what crosses over from a stranger saying “hi” to street harassment is when their words or actions sexualize the person they’re addressing and the interaction becomes intrusive and inappropriate.

“From hello to more vulgar comments, catcalls sexualize and objectify people without their consent,” Sandberg said. “This has to do with tone, context and physical cues like looking someone up and down.”

Sandberg says the chalking has elicited a range of bystander reactions, from upset to shocked. She has received comments from men who didn’t realize how much of a problem catcalling is. Some have even asked for resources, and she sends them bystander intervention training from fellow anti-harassment nonprofit Right To Be, so they can speak up the next time they witness a catcall.

“People who didn’t know this was happening all of the time are our target audience,” Sandberg said. “With awareness and training, they can now step in and make people feel safer.”

The impact of catcalls

Like many other women, Sandberg had long believed the catcalling was her fault. She wondered if her dress was too inappropriate, too short and if it revealed too much — it changed how she felt being in a public space wearing what she wanted to wear.

“As a woman and a queer person, there’s kind of a protective layer that you wear walking down the street because of catcalling and harassment,” she said.

Women can begin to internalize an objectified view of their own body after repeated exposure to catcalling, according to psychologist and Stetson University professor Christopher Ferguson, who co-authored a study on the effects of the harassment. They may “begin to value themselves based primarily on their own sexual appeal to other men,” he said. “This has a lot of downstream negative impacts on women’s self-esteem.”

This repeated focus on the body can cause mental health issues like depression, anxiety and eating disorders, according to Helen Wilson, a clinical psychologist at Stanford Medicine.

“These experiences are unwanted, unpredicted and threatening, and often occur in vulnerable, unavoidable situations such as walking down the street at night,” Wilson said. “Therefore, they also are frightening and disrupt a person’s sense of safety and security.”

Sexual harassment is a means of asserting control and dominance, said Wilson. She believes the work of Chalk Back offers a way to flip the power dynamic, where the people who experience harassment can tell their stories publicly — the “objects” become the authors.

“Part of recovering from trauma involves finding ways to take back power and agency over an unwanted, out-of-control experience,” Wilson said.

The growing movement to end catcalls

In recent decades, there has been greater awareness of the impact of street harassment. Catcalls of NYC is just one of several movements.

Right To Be, formerly Hollaback!, has been working to end harassment since 2005 through intervention training and story collection. Stop Street Harassment started as a blog in 2008 and became the nation’s only hotline for people facing street harassment. SlutWalks have taken place around the world in the wake of a Toronto police officer who said to York University students in 2011 that women should avoid dressing like “sluts” to prevent being sexually assaulted. The Toronto Police Department called his comments unacceptable and the officer later apologized.

Holly Kearl, founder of Stop Street Harassment, believes ending street harassment must involve a multi-faceted approach. “We need awareness-raising campaigns like Catcalls of NYC, but we also need more education on the issue, better policies and more efforts targeted at boys and men since they are the main perpetrators of the harassment of people of all genders,” Kearl said.

Approaches also need to be adapted based on culture and location. When Malvina Ghidetti, the 26-year-old co-founder of Catcalls of Turin in Italy, discovered Sandberg’s initiative, she wanted to implement something similar but adapt it to Turin’s cultural context and needs. She said there is a well-known stigma around catcalling in Italy, as it is often dismissed as a compliment, instead of an unwanted burden that can take a mental toll.

Processing the effects of catcalling “in a safe space was very important,” Ghidetti said. “Being a part of Chalk Back really made me realize how much interconnectedness there is and how it’s a feminist issue.”

In 2018, France became the first country to outlaw sexual or sexist comments that are “degrading, humiliating, intimidating, hostile or offensive.” Harassment on streets and public transportation is now subject to fines of $105 to almost $900.

While catcalling isn’t banned at the federal level in the U.S., laws on street harassment vary from state to state. In New York, gender-based discrimination is illegal, and five laws prohibit some form of verbal harassment including disorderly conduct and harassment in the second degree. The penalty ranges from 15 days in jail to one year in prison.

Ferguson not only believes it would be hard to make catcalling a federal crime, as even hate speech is protected by freedom of speech, but he also doesn’t think it would end catcalling.

“If a man was following a woman, then it goes beyond harassment, that might be a criminal offense, but I think just in terms of like the stereotypical construction worker whistling at a woman, I don’t know if we want more people in jail,” Ferguson said. “Our answer to everything in the U.S. shouldn’t be to make it a crime.”

Ending catcalls through education

Sandberg said Catcalls of NYC is not pushing for any type of legislation because the group believes cultural change and education are the core aspects of changing the culture of harassment. She said while she wants catcalling to become less acceptable, she also believes criminalizing it would largely impact low-income communities of color.

In 2014, a viral video from Hollaback! showed a woman walking around New York being catcalled numerous times. The video consistently showed Black and Hispanic men catcalling, while white men had been edited out, leaving critics to say the video was “demonizing men of color.”

Catcalls of NYC, and the Chalk Back movement as a whole, are primarily focused on a long-term solution that will address the systemic issues behind catcalling, including a lack of education and access to mental health services.

“Sharing these stories allows people to go from feeling less alone to feeling more empowered to talk about it with their friends and bystanders,” Sandberg said. “This movement really has a ripple effect in terms of targeting people and impacting people who face harassment.”

At a recent event for International Women’s Day, Sandberg and two Catcalls of NYC volunteers were chalking at Washington Square Park. “Hey sexy, I’d like to see you with that skirt off,” Sandberg wrote. She stood up and dusted off her chalky hands. As she began looking through other submissions, trying to choose the next catcall to chalk, passersby stopped to read the quotes. Some even took photos. The more Sandberg and volunteers chalked, the more a crowd developed.

What 23-year-old volunteer Samantha Donndelinger appreciates about Catcalls of NYC is that it holds catcallers accountable while creating a supportive space for those impacted to share stories and change the narrative.

“I think the more that people take it seriously, that is the next step forward to creating safer streets and being able to smile at strangers again,” she said.