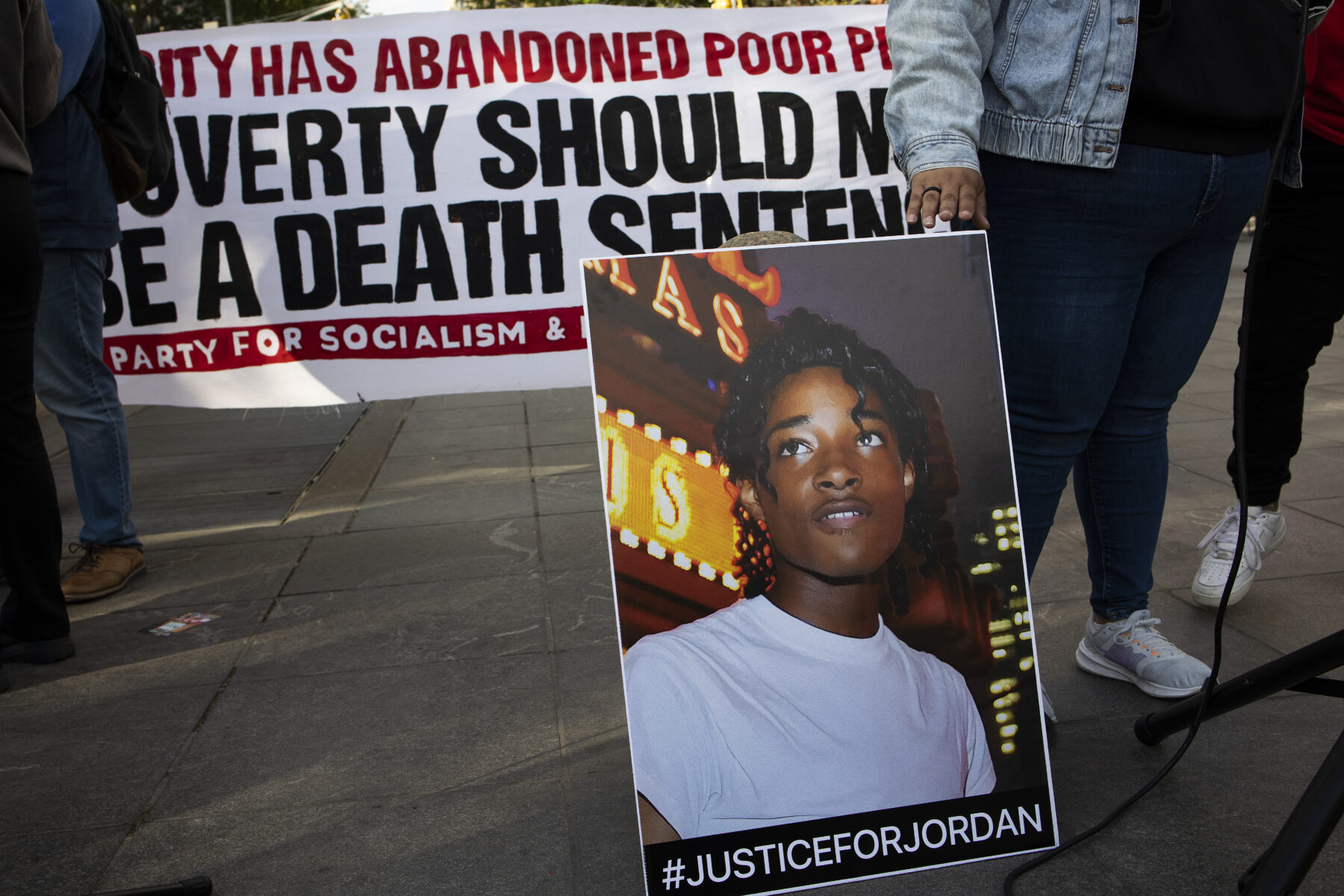

The killing of Jordan Neely, the Black homeless street performer who was choked to death on the New York City subway last month, has made countless headlines. It has also raised issues about how journalists can better report on mental health.

On May 1, witnesses say Neely had been shouting at passengers but hadn’t touched anyone, when white Marine Daniel Penny put Neely in a lethal chokehold for 15 minutes. Some news outlets initially stumbled over how to frame the killing in headlines and ledes, instead focusing on Neely’s mental illness. One called Neely a “disturbed man” who got into “a brawl with the wrong passenger.” Other newspapers and news broadcasts labeled Neely “unhinged” and “acting erratically.”

Psychologists and ethics experts say such media coverage not only takes the onus off the killer, but it also stigmatizes mental illness. “Using words such as ‘aggressive,’ ’unhinged,’ and ’erratic’ plays into the fear that people have regarding mental health conditions,” said Azizi Marshall, a licensed counselor who specializes in ethical communication.

She advises journalists to avoid using labels when reporting on people believed to have mental health conditions. “These terms reinforce negative stereotypes and contribute to the discrimination against people experiencing mental health challenges,” she said.

The stigma also has real-world effects on people experiencing mental illnesses. “This could prevent them from getting support because they don’t want their family or friends to view them as ‘unhinged,’ ‘crazy,’ or even ‘dangerous,’” said Jasmine Bishop, a licensed counselor in Arkansas.

Below, Bishop, Marshall and other mental health and ethics experts explain how journalists can more responsibly cover mental health — including when to mention it at all.

Stop writing sensational headlines

In a click-hungry media landscape, “sensational and emotional words are what grab people’s attention most easily,” said Dr. Bruce Bassi, a psychiatrist who consults with journalists on the ethical portrayal of mental health disorders. For example, a headline saying “crazy man choked on the subway” will likely attract more attention than “homeless man with a history of mental illness attacked on the subway.”

A lack of awareness is another reason harmful language gets published. There are few official trainings and resources that teach journalists how to responsibly cover the mental health beat — but they do exist.

The Carter Center has a comprehensive database of resources on covering mental health and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard offers tips for responsible reporting. The Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas has an online course that not only covers reporting on mental health, but also journalists taking care of their own well-being.

Ideally, if a newsroom doesn’t have a standards department checking for sensitivities, journalists should consult with psychologists and ethics experts before publishing news about mental health. Bishop said it’s important to speak to professionals trained to do the work, rather than someone who has a large following.

Avoid stigmatizing language

The easiest way newsrooms can start covering mental health responsibly is by paying attention to the words used to describe people who experience mental illnesses.

Every expert NBCU Academy spoke with advised journalists to steer clear of derogatory words like:

- Crazy

- Mad

- Erratic

- Unhinged

- Idiot

- Nuts

- Freak

- Manic

- Deranged

- Stupid

- Psychopathic

- Schizo

- Druggie

- Junkie

- Retarded

Bassi advises journalists to refrain from using any terms that end in “ic” like “psychotic” or “sociopathic,” unless they can actually verify someone’s diagnosis.

Words like “bipolar,” “trauma,” “gaslighting,” “narcissistic” and “anxious” also tend to be misused and overused in pop culture and the media, said Bishop. For example, usage of the hashtags #gaslighting and #trauma are in the millions on social media, with the former declared by Merriam-Webster as its “word of the year” in 2022. This glamorizes dangerous behavior and makes it challenging to determine what’s normal and when to seek help.

To make sure journalists are portraying mental health struggles responsibly, Bassi recommends that journalists pause and ask whether a description is a judgment or a pure observation.

“Think of an observation as if you were describing what you see to someone who cannot see it, versus a judgment as an inference of what is not visible,” he explained. For example, instead of saying “crazy behavior,” journalists should describe what the behavior is — shouting, running, swearing, etc.

Experts also recommend avoiding saying someone is “a victim of” or “suffering from” mental illness. “These phrases can be disempowering and suggest that people with mental health conditions are helpless,” said licensed therapist Bre Haizlip. “Instead, use language that highlights resilience and agency.”

So instead of saying, “he suffered from depression,” journalists can say “he experiences depression,” or “he is diagnosed with depression,” if they verify the person’s condition.

John Delatorre, a forensic psychologist and news commentator, also advises journalists to avoid saying someone “committed” suicide or “took their own life,” as these phrases imply someone “committed” a crime. “Suicide happens as a result of a prolonged time of distress,” he said, so it’s important not to denote it as a sudden decision.

“Instead, use neutral language such as ‘death by suicide’ or ‘as a result of suicide,’” Haizlip said.

Don’t make assumptions

Overall, never make any assumptions about someone’s mental state or attribute their crimes to their diagnosis.

“Never link the behaviors engaged by a person to their possible mental health as there are many reasons why people do what they do,” Delatorre said. “Until you get the diagnosing clinician to comment, nothing is confirmed.”

Even if you can’t verify the mental health history of the people you’re reporting on, it’s important to provide context to the incident. For example, Neely’s killing was a layered story.

Journalists should paint the full picture, including the many systemic issues at play (houselessness, poverty). Even though Penny said the killing had “nothing to do with race,” there are racial dynamics that can’t be ignored (America has a long history of white men taking Black men’s lives) as well as the tensions over how to solve New York City’s rising mental health crisis (some want to add more police in public spaces; others say the city needs to address systemic problems instead).

These are important details that journalists must describe so readers fully understand what’s happening beyond “something crazy happened on the NYC subway.” As Haizlip said: “Aim to tell the whole story by providing context, including the possibility of past trauma and contributing sociocultural factors at the intersection of the story.”