Up to 1 in 4 adults in the U.S. have a disability. Not all disabilities are visible, and not all are physical. They can be cognitive, such as anxiety, autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Being disabled doesn’t inherently mean you’re incompetent, but a lot of us struggle with that assumption. If you have a disability, deciding whether to tell your co-workers and friends can be difficult. Will it influence the way they think of you? Will it affect how you’re treated in the workplace?

Thanks to the Americans with Disabilities Act, we know the answer to that last question.

This month marks the 33rd anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act. It’s also Disability Pride Month, celebrated every July for the passage of the legislation. In March 1990, more than 1,000 people marched from the White House to the U.S. Capitol to demand the passage of the ADA to provide civil rights protections to people with disabilities. Then-8-year-old Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins got out of her wheelchair and crawled up the Capitol steps, along with other activists, to highlight inaccessibility issues. More than 100 people were arrested, many carried away in wheelchairs. Three months later, on July 26, President George H.W. Bush signed the ADA into law.

The law, which defines someone with a disability as “a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity,” has five critical parts to ensure equality. The first title covers employment, from hiring to training to conditions. The second ensures that state and local governments offer effective communication for people with vision, hearing and speech disabilities; provide accessible public transportation for those with physical disabilities; and identify and correct any architectural barriers, like offering elevators and ramps.

Title III ensures that private and public places — including restaurants, retailers and day-care centers — offer accessibility. Title IV, regulated by the Federal Communication Commission, focuses on communication. For example, the FCC makes sure closed captioning exists for public service announcements and that all telephone and internet companies provide telecommunications relay services so people with hearing and speech disabilities can communicate. The last title focuses on miscellaneous provisions such as retaliation and coercion, and the impact on insurance providers and benefits.

In 2008, the law was expanded with the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act, which made significant changes to the definition of “disability” to be more inclusive. An employee can be regarded as having an impairment even if the employer doesn’t think the impairment is limiting. For example, the ADAA protects individuals who are in remission or who have an impairment that occurs episodically. The law also broadens out “major life activity” to accommodate bodily function impairments relating to the immune system, such as digestive issues and problems sleeping and standing. Disabilities continue to be added under the ADA and the ADAA.

As someone who has benefited from workplace accommodations, I can’t stress enough how important it is to be protected legally. It can be something as little as a stipend to get office supplies to keep you more focused if you have a mental disability, or mental health days when you’re feeling burned out, or specialized desks or ramps to help you function to the best of your abilities in your workplace. These resources make a huge impact in the lives of the people who need them.

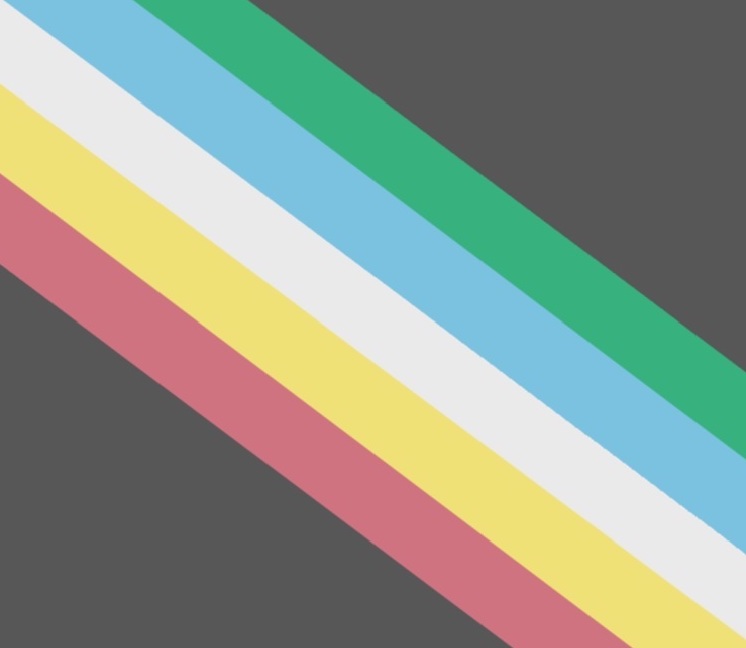

Just as the ADA has evolved to become more inclusive, so has the Disability Pride flag. The original banner, created in 2019 by disabled artist Ann Magill, was black with five zigzag stripes of light blue, gold, white, red and green. But in 2021, she noticed the zigzag design, when viewed online, created a strobe effect that could instigate migraines or seizures for those with epilepsy. She then worked with the disabled community on Tumblr to create today’s inclusive flag, now a charcoal gray with the line colors softened and straight diagonal lines replacing the zigzag stripes. The flag’s five colors represent the different types of disabilities: red (physical disabilities), gold (neurodivergence), white (invisible and undiagnosed disabilities), blue (psychiatric disabilities) and green (sensory disabilities).

When one thinks of remarkable people with disabilities, they often think of Professor Stephen Hawking, one of the most celebrated theoretical physicists the world has ever seen. Or Helen Keller, an amazing woman who was able to communicate despite growing up blind and deaf, and who would go on to graduate from Radcliffe College and co-found the ACLU. But these are only two examples from a vast pool of people who have so much to give.

We want the world to recognize that our disabilities – seen and unseen – are an integral part of who we are. It’s about accepting that our disabilities do not make us lesser than anyone.

In the words of disability champion Lachi, who performed in a special NBCUniversal event in April, “Let’s start thinking outside the box because we’re already not in the box. Folks with disabilities should celebrate the fact that we’re the disruptors. We have disruptive ability, and that’s what the ‘dis’ stands for. We’re the blue butterflies in a sea of red butterflies.”

This July, I encourage you to stop and think about how far we’ve come, how far we’re going to go — and how, as a culture, we’ll get there. The sky’s the limit. Happy Disability Pride Month.