Swara Salih, a 32-year-old Kurdish American, has been reluctantly ticking “white” on federal forms his whole life. But that’s not what he sees when he looks in the mirror.

“My entire life I’ve been a brown kid, I’ve had darker skin than my white friends,” Salih told NBC News. “I was very culturally confused in that way as a kid, like, ‘What am I supposed to be?’ I’m not white, I’m not Black, I’m not Latino.”

The new Middle Eastern or North African category announced by the Office of Management and Budget on Thursday will help shed the cloak of invisibility draped on members of the community, like Salih, for decades, experts say.

The addition of this category to the OMB’s standards for race and ethnicity for the first time in U.S. history means that an estimated 8 million Americans who trace their origins to the Middle East and North Africa will no longer have to choose “white” or “other” on federal forms, including the U.S. census.

“We were forced to identify as something we were not, and in a way that erased the community and erased any data on the community,” said Abed Ayoub, the national executive director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), one of the first advocacy groups to push for an identifier for MENA Americans. “We’re a different community and we have not been able to — since we’ve been here — get an accurate picture of who we are.”

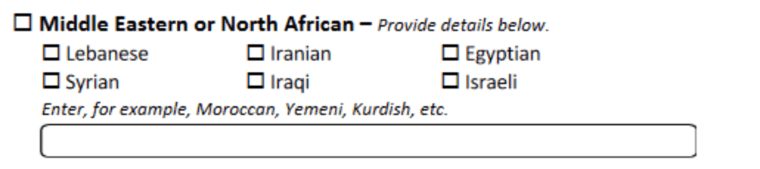

The new identifier will have six subcategories beneath it that include Lebanese, Iranian, Egyptian, Syrian, Iraqi and Israeli, which were selected to represent the largest population groups in the U.S., an OMB spokesperson said. The identifier will also include a blank space where people can write in how they identify if their ethnicity isn’t one of the subcategories.

While advocacy groups don’t think the geographical addition goes far enough to capture the diversity of the region, they say it’s a long-awaited step in the right direction.

Undercounted, underrepresented and unnoticed

The lack of an identifier for Americans from the Middle East and North Africa has left them undercounted, underrepresented and unnoticed in U.S. society.

MENA Americans can trace their origins to more than a dozen countries, including Egypt, Morocco, Iran, Turkey and Yemen. The region is racially, ethnically and religiously diverse, and people from there can be white, brown or Black, as well as identify with an ethnic group, like Arab, Amazigh, Kurdish, Chaldean and more. Migration from countries in the region to the U.S. began in the late 1800s and picked up in recent decades largely because of political turmoil, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

The largest MENA group in the U.S. is Arab Americans, according to data collected by advocacy groups. The new identifier came days before the start of Arab American Heritage Month on April 1.

Tariq Ra'ouf, 33, a Palestinian American, described feeling like his identity was being erased when having to tick “white” on job applications.

“When I’m filling them out it’s like, ‘This is ridiculous,’ because I’m not white,” Ra'ouf said. “And then, if I say that I’m white, I might lose out on opportunities at companies who are looking to hire culturally and ethnically diverse employees. Who knows how many applications people might have missed because they are forced to put down a race that doesn’t represent them.”

The MENA and white communities are different in many ways, including culturally, socioeconomically and politically. A MENA identifier will help federal agencies collect crucial data that will in turn improve policy decisions, said Maya Berry, the executive director of the Arab American Institute (AAI). The lack of an identifier has meant that research on the community has largely been anecdotal, and it led to its members losing out on federal resources such as health and social services.

“That category is the way that we address that our community has been rendered invisible in the data for decades,” Berry said. “There’s a direct harm when communities do not have the kind of information that is needed about them, anywhere from the issues that we saw during the Covid pandemic, to the way congressional districts are drawn, to health research about our folks, to protecting our civil rights.”

Even the 8 million MENA Americans that advocacy organizations estimate live in the U.S. may be an undercount, Ayoub says.

“We’re going to have clear data on the number of folks from the region that are in this country, where we live — everything from our spending habits to health issues to education,” Ayoub says of the addition of the identifier. “In this day and age, you really need data to be a strong advocate for your community. And this will allow for us to get a better picture of who our community is.”

Ra'ouf is excited he won’t have to misrepresent himself anymore.

“I think it’s about time,” he said. “It’s a little frustrating that it took so long to get to this point. But mostly, I think it’s just exciting because we’ll be able to truly get a bigger sense of how many of us there are in this country, and get better representation.”

A decadeslong effort

Getting a MENA identifier on the census has been a decadeslong, back-and-forth effort by groups such as the ADC and AAI.

The Census Bureau had already tested the category in 2015 and found it yielded data that provided better insight into the MENA community. The category was abandoned when the Trump administration came to power.

The OMB announced the long-awaited update more than a year after the Federal Interagency Technical Working Group on Race and Ethnicity Standards recommended adding the identifier as a new category. This is the first time the OMB has updated the standards for race and ethnicity since 1997; prior to this change, there were five categories for data on race and two for ethnicity: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; White; Hispanic or Latino; and non-Hispanic or Latino.

The OMB instructed all federal agencies “to begin updating their surveys and administrative forms as quickly as possible,” according to a statement. Federal agencies have five years to bring all data collection into compliance with the updated standards, which means Americans can begin seeing this update in documents within that time.

Berry says we may see a “ripple effect” in which nongovernmental institutions, such as hospitals and universities, adopt the OMB’s new standards.

“Let’s say I’m a hospital and I want to apply for federal research grants. I would absolutely make sure that I was matching federal standards,” Berry said. “I can’t imagine a single aspect of our society — companies, health institutions, universities, corporations — that’s not going to want to be aligned with federal standards.”

Not a perfect solution

Experts warn that the category is not the exact solution they were advocating for, and could lead to another undercount of the diverse community in the U.S.

Countries such as Somalia and Sudan are included in the 22 countries that make up the Arabic-speaking world, according to the ADC, and many hailing from those nations identify as Arab as well as African. But the OMB’s new category does not include a way for Afro-Arabs to identify themselves, a sticking point for experts who weighed in on the change.

“Let’s say I’m Sudanese — I check MENA because I identify ethnically within the MENA category and I write ‘Sudanese’ in the space,” Berry explained. “I am not sure that they will still be coded within MENA, because the code for Sudanese now is Black or African American.”

Prior to the existence of a MENA category, many MENA Americans would tick “other” on the census, write in their identities and be tallied into the white community anyway — Berry worries the same will happen to Afro-Arabs.

“And just like before, we didn’t want to be exclusively white. Moving forward, we can’t have a category that excludes Afro-Arabs from being part of MENA if that’s how they want to identify,” Berry said.

While people are free to tick more than one box, it’s not clear how hyphenated MENA identities will be tallied, Berry said.

Ayia Almufti, a 25-year-old Iraqi American, disagrees with the use of the term "Middle East" for the category, which was coined and used by European officials in the 19th century for the region in accordance with its proximity to Europe.

"I prefer SWANA (Southwestern Asia and North Africa) any day," she said, adding that the new category is still an upgrade.

Ayoub also warned of not including Armenian Americans in the MENA category, many of whom were forced to relocate to countries in the Middle East during the Armenian genocide and may identify ethnically as Middle Eastern.

A way to have avoided this would have been to let the Census Bureau, which conducts the statistical research on race and ethnicity, formulate the category question based on its findings, said Berry.

In a statement, the Census Bureau said it follows standards set by the OMB and that it will develop plans to implement it in censuses and surveys, like the annual American Community Survey and the decennial census.

Both Berry and Ayoub say they will continue to advocate for better representation of the community.

For now, Ra'ouf hopes this update will give future generations what he didn’t get growing up.

“The feeling of actually being able to check off what you actually are is a feeling that I think none of us really have gotten to experience,” Ra'ouf said. “And I think for the kids, and everyone growing up and filling out those boxes in the future, I hope that it will add some sense of pride.”

Even though it’s not a perfect category, Salih says it beats having to identify as white without benefiting from the privilege that it offers, especially against the backdrop of anti-Arab and Islamophobic sentiment.

“I think that it allows us to assert our identities in a society which has by and large wanted to shun us, to ban us from coming here,” Salih said. “But now we’re able to say more officially, ‘No, we are here. We exist.’”