Dr. Dale Okorududu still remembers sitting on a plane on his way to a cousin’s wedding when an older white woman asked him why he wore baggy clothes. You shouldn’t wear that, she said. Okorududu, now 40, was a college student at the time, dressed in sweatpants and a sweatshirt. He pulled his chemistry books out of his bag, hoping to end the woman’s line of questioning. That’s when she asked him if he was a drug dealer.

Okorududu corrected the woman, buried his head in his books and counted the minutes until he could get off the plane. Over the next few years, he would graduate from the University of Missouri-Columbia and complete his residency at Duke University School of Medicine.

Today, he is a board-certified pulmonary and critical care doctor at the Dallas VA Medical Center and an associate professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center. He is also the co-founder, along with his brother and fellow doctor, Daniel, of Black Men in White Coats, a nonprofit aiming to increase Black male representation in the medical field.

“There are always people trying to place expectations on us as Black men,” Dale said. “They want to shake us up a bit.”

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, Black men make up less than 3% of physicians in the U.S., even though Black men make up over 6% of the population. It’s a number that has been stagnant for nearly a century — Black men made up 2.7% of doctors in 1940.

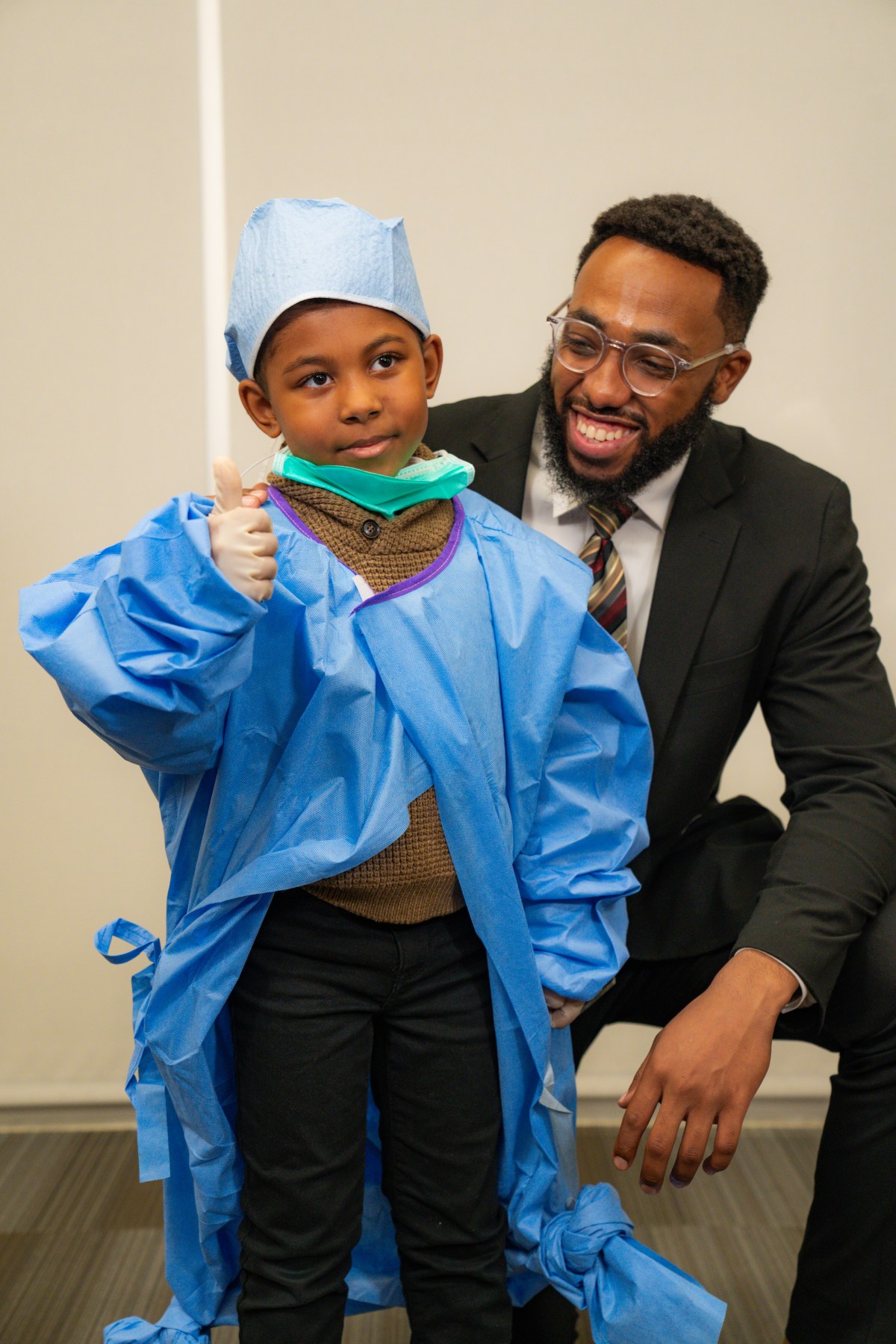

Black Men in White Coats is working to raise that percentage in several ways, including producing a documentary series and podcast featuring Black male physicians who have found success despite racial and financial barriers. The group also offers mentorships to Black medical students and hosts youth summits on educational resources for medical school admissions, financial aid and medical fields of study. While the program was initially geared toward Black males because of the stereotypes thrust upon them, it’s now open to all genders. They want Black kids to see that medicine is a career option — one that can also serve their community.

“During the summits, we try to create a village where we also bring parents in and teach them ‘this is what your kid should be considering at this age,’” said Daniel, 42. “We make sure they are also aware of the struggle and sacrifices that a kid is going to make.”

De’Larrian Knight, a UCLA medical student and member of the university’s chapter of Black Men in White Coats, said joining the organization aligned with his goal of a career in serving communities of color and helping to gain trust in the medical community.

“I realized I found an organization that was dedicated to not only increasing the number of Black men in medicine, but to teach them the hidden curriculum in how to navigate medicine as a pre-med student,” Knight said.

Reckoning with a history of medical mistreatment in Black communities

There is a long history of mistreatment of Black people in the American medical system, which has led to great distrust in Black communities toward medical professionals.

Among the most unethical violations in U.S. medicine was the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” From 1932 to 1972, 600 Black men — 399 who had syphilis and 201 who did not — were enlisted in a government-funded experiment. Without the participants’ consent, researchers told them they were being treated for “bad blood.” It resulted in the death of 128 participants, 40 wives being infected and 19 children being born with congenital syphilis.

Disregard for Black peoples’ health and concerns continues to permeate medical settings today, said Margaret Vigil-Fowler, a historian of race, gender and medicine. According to a 2022 Pew Research Center report, about 3 in 10 Black adults say they’ve felt rushed by their health care provider, and 29% said they’ve felt they were treated with less respect than other patients.

“There is unfortunately such a long history of both experimentation on Black patients and not taking their concerns or symptoms nearly as seriously as white patients,” said Vigil-Fowler, who recieved her doctorate in history of health sciences from the University of San Francisco. “All of these things happened at the hands of white physicians, so there are very good reasons that the Black community is going to distrust.”

As Vigil-Fowler points out, exacerbating this issue is the lack of Black doctors for Black patients to turn to. According to a recent Stanford Health study, Black men take more proactive health measures, such as flu shots and diabetes screenings, when treated by a Black doctor.

The lack of Black doctors can be traced, in part, to the publication of the 1910 Flexner Report, a study commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation that examined the state of U.S. medical education. The report noted the shortcomings of medical schools at Black colleges, suggested Black physicians were inferior to white ones and recommended that Black physicians should only be trained to serve Black communities. Many medical schools couldn’t meet the report’s standards, and five of the seven medical schools at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) shut down.

HBCUs were “really the only pathway that most Black Americans had for earning medical degrees because admissions policies at other schools often excluded them,” Vigil-Fowler said. Once those programs were gone, so were the opportunities for Black people to become doctors.

The American Medical Association also effectively excluded Black doctors for more than century by only giving memberships to those who already belonged to a local medical society — and many local societies didn’t allow Black physicians to join. (The organization has since apologized for its past behavior and pledged to right its wrongs.)

“When you look at the historical record, it [AMA] bears a lot of responsibility for the shortage of Black men in medicine and the lack of mentorship and role models,” Vigil-Fowler said. “There’s now a lack of institutional knowledge.”

This year, the Student National Medical Association, in a statement, called for action on the urgent need for targeted efforts to eliminate the shortage of Black male physicians. They recommended expanding the size of medical school classes, diversifying admissions committees through increased hiring of Black medical faculty and creating affordable preparatory programs to create a more supportive network.

“People who do better on their path to becoming a physician are often more well-resourced and equipped,” Daniel Okorududu said. “The main issue is that we don’t often have the resources for test prep, textbooks and exams. At Black Men in White Coats, we are scoring mechanisms to better resource and equip students so they are ready to apply to medical school.”

Offering resources and mentorship to young Black men

As Daniel noted, one of the biggest barriers for Black men becoming physicians is financial. Knight, the UCLA student, said the high costs of his education, taking the MCAT exam and application fees were a significant challenge for him.

To overcome this, Black Men in White Coats, in partnerhsip with Diverse Medicine Inc., a nonprofit working to increase diversity in the medical field, has reimbursed over $200,000 of students’ MCAT fees. During the nonprofit’s youth summits, students also learn more about the financial burden of medical school and how they can protect themselves from going into debt. Students can also create a mentor network by speaking with panelists at the summit or requesting a mentor through the organization’s online portal.

“I use the lack of Black men in this field as motivation, but the experience on this journey so far has made me feel lonely,” said Isaiah Smith, a student at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a member of Black Men in White Coats. “There are just too few people on this journey who look like me, but knowing that I have Black Men in White Coats rooting for my success makes it all worth it.”

Other organizations like Black Men in Medicine, the Association of Black Women Physicians and the National Medical Association also help Black people get into the medical field. While Black Men in White Coats was created following a 2013 Association of American Medical Colleges report showing a decline in the number of Black men applying to medical school, the Okorududu brothers recognized that the numbers for Black women were also low and decided to open up membership to all in the Black community.

Daniel said they kept the emphasis on Black men, though, because of the “narratives pushed” on Black boys to be professional athletes or creatives, not medical professionals. He said he was the only Black man in one of his medical school classes of 200 people, which also had less than 20 Black women. He knew he had to do something about those numbers and inspire greater representation.

Today, Daniel says he sees the results every time a Black patient’s face lights up when he walks into the room.

“The first thing they say is that they feel a lot more comfortable speaking with me,” he said. “At the end of the conversation, I can tell they are saying they can trust me and that they’re going to listen to what I’m saying.”

Dale said one of his biggest motivations in creating the organization was providing this added layer of trust for Black patients.

“I would tell a young Black man interested in medicine not to quit,” he said. “There’s a patient out there that you don’t know about yet, who, in 15 to 20 years, is waiting for you to take care of them.”